Language, Identity, and the Problem of Shared Words

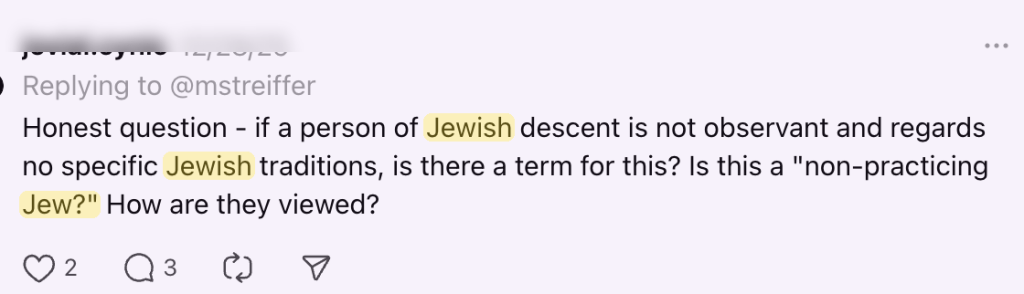

“I’m a secular Jew.”

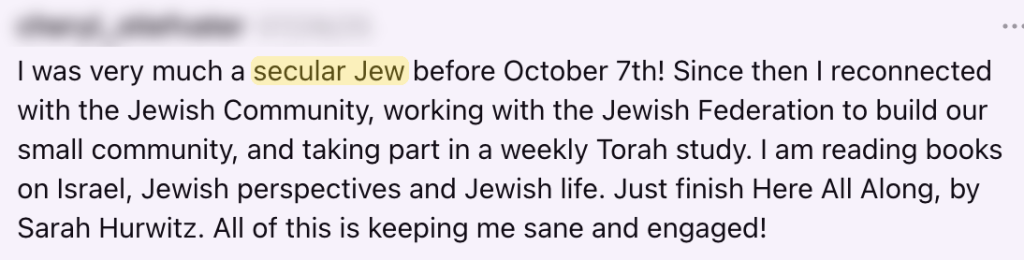

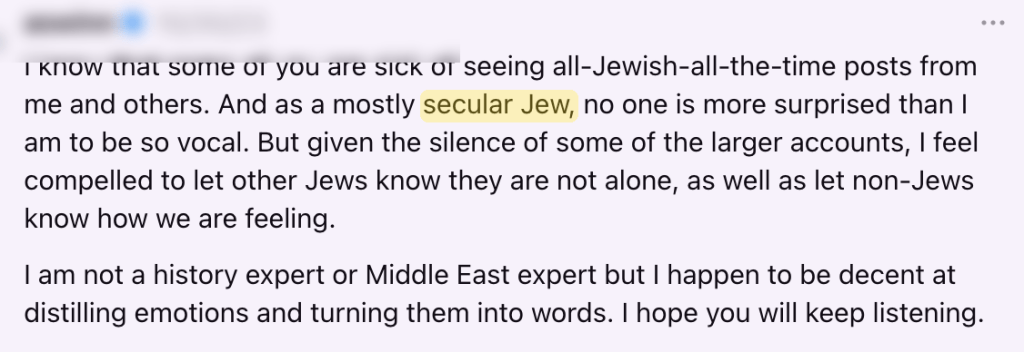

It’s a phrase that appears constantly in American Jewish life. People use it as shorthand. Sometimes as a disclaimer. Sometimes as protection. Sometimes because it feels like the only available option when none of the familiar denominational boxes fit.

The problem is not that people use the term.

The problem is that we assume it means the same thing to everyone who hears it.

It doesn’t.

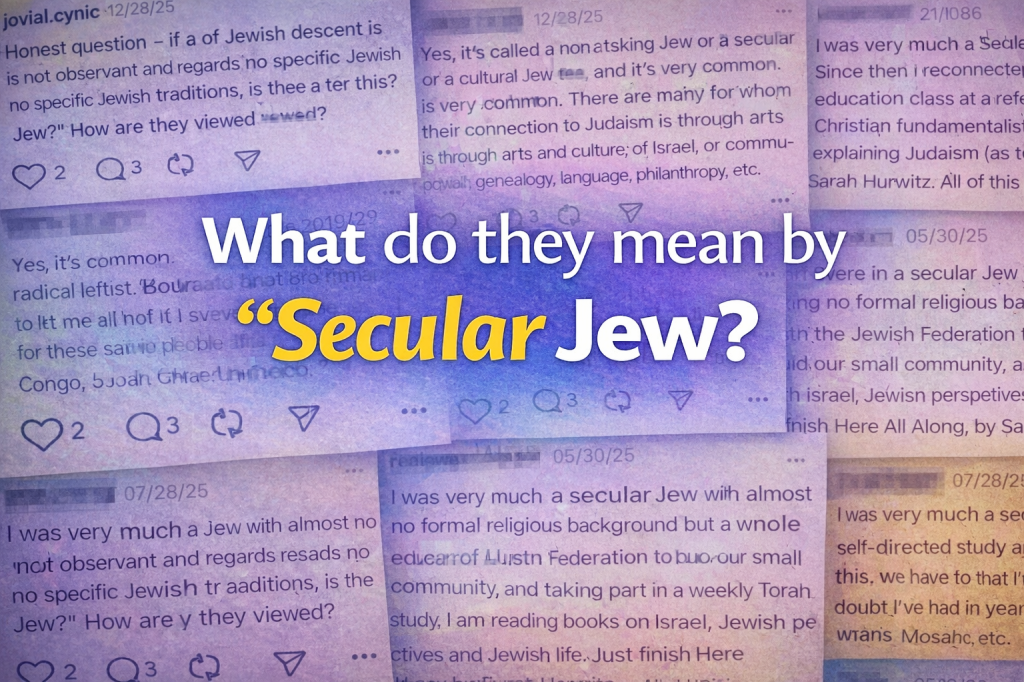

Due to the sheer number of times I have read social media posts using this identifier, and the assumptions and miscommunications that arise, I wanted to tackle its use, misuse, definitions (multiples of them), and a possible suggestion for other linguistic identifiers that are more aligned. This piece is not an attempt to redefine “secular Jew,” but to surface how differently the term is heard, used, and operationalized across contexts.

How Hiloni can help

To understand why the word secular is so unstable in American Jewish life, we have to start in Israel.

In Israel, Jewish identity historically developed within a relatively stark framework. You were either religious or observant, usually Orthodox, or you were not. Those who were not were labeled hiloni, typically translated as secular.

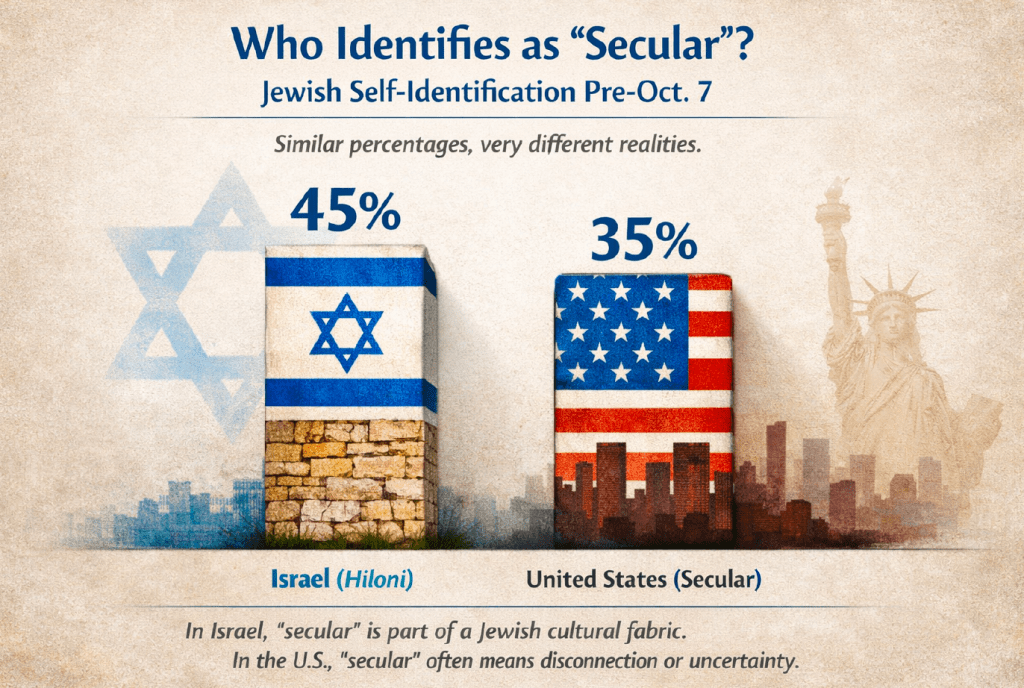

According to the Israel Central Bureau of Statistics, roughly 42–45 percent of Israeli Jews identify as secular or hiloni. On paper, that number looks similar to American Jewish data.

In lived reality, it is not.

Israeli Jews who identify as secular routinely:

- fast on Yom Kippur, at least partially

- attend Passover seders

- light Hanukkah candles

- have mezuzot on their doors

- mark Jewish holidays as part of family and public life

The Pew Research Center’s Religion in Israel study documents this clearly. The Jewish People Policy Institute (JPPI) has repeatedly emphasized that in Israel, hiloni primarily describes a relationship to religious authority, not a withdrawal from Jewish life (see here).

In Israel, Jewishness is ambient. It is embedded in the calendar, the language, the public sphere, and national life itself.

Jewish Time: Embedded vs. Opt-In

This structural difference matters more than we often acknowledge.

In Israel, Shabbat is not Saturday with Jewish meaning layered on top of it. It is Yom Shabbat, the day itself. The week moves toward it. Public life slows around it. Even Israelis who do not observe Shabbat ritually live inside its rhythm. In the United States, Shabbat must be consciously overlaid onto Saturday, a day already shaped by work, errands, sports, and social obligations. Observance requires opting in.

The same is true for modern holidays.

For American Jews, Yom HaZikaron and Yom HaAtzmaut are often experienced as Jewish holidays, marked in synagogues, schools, camps, and community spaces. In Israel, they are national days. Sirens sound. Schools close. Public ceremonies unfold everywhere.

Yom Kippur makes the contrast unmistakable. In Israel, the country shuts down. In America, individuals must choose to set the day aside.

And Jewish education (Jewish history and TaNKh studies, etc.) is another stark difference. Jews in America either attend a Jewish day school to learn these topics or they are enrolled in supplemental Jewish education (aka religious school) to learn. In Israel, these topics are taught even in the “public” schools. Of course, Hebrew is an obvious difference, of American Jews having to opt-in to learn it.

These differences shape how people understand themselves as Jewish and how they use words like secular.

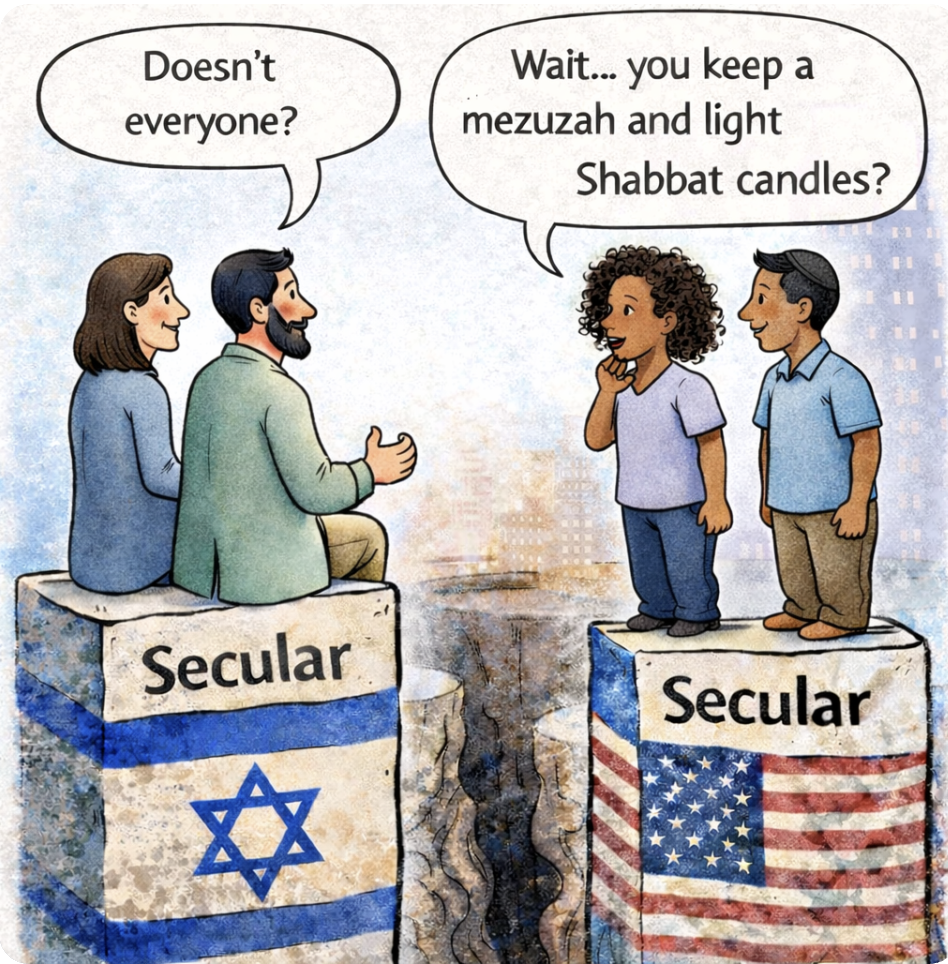

The Mifgash Moment

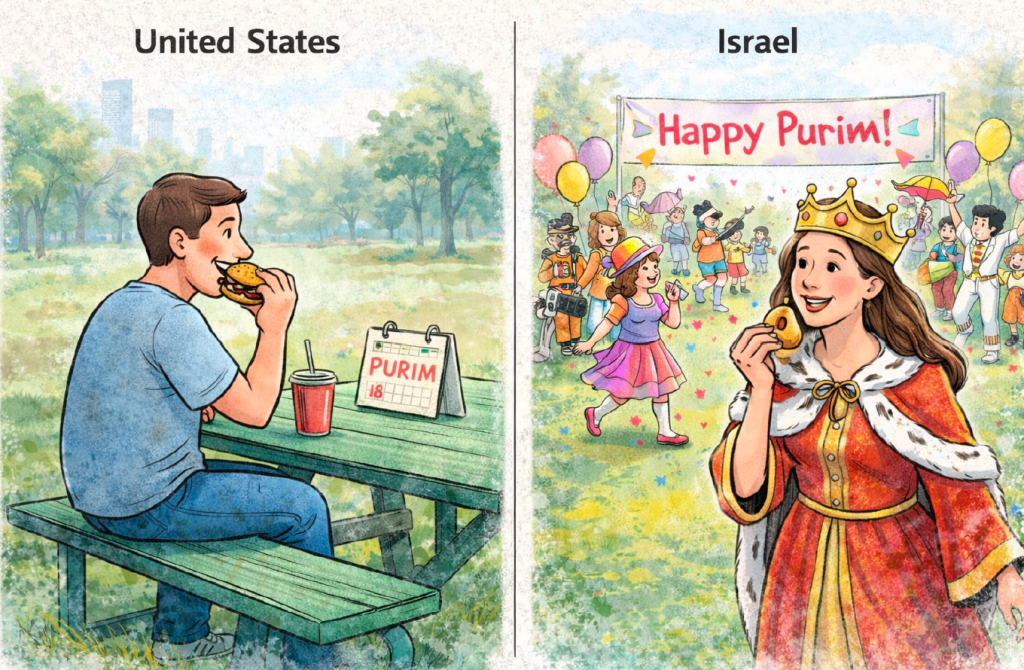

I have watched this gap surface again and again in mifgashim, encounters between Israeli Jews and American Jews. In almost every one I have facilitated, (before 10/7/23) a conversation emerges like this:

An Israeli Jew says, “I’m secular.”

An American nods, assuming shared meaning. But then curiosity emerges for the American, because how could an Israeli Jew not be engaged at all in Jewish life (because that is how we often interpret the word in the States.). So the questions begin:

A: “Do you fast on Yom Kippur?”

I: “Yes. And we go to the synagogue.”

“Does your family have a Pesach seder?”

“Of course. It’s never not done.”

“Do you celebrate Purim?”

“Oh it’s a HUGE festival and we all dress up and have parades in the streets and parties in the park.”

“Well, do you light candles and have Shabbat kiddush?”

“Yes, my family does together, and then I go out with my friends.”

“Well then, I guess you aren’t familiar with Torah portions and other Jewish education.”

“Oh, no. We learn that every day in school.”

But now the American Jew is more confused, because an assumption is that a Jew in America who defines themselves as secular doesn’t do these things. So then conversation switches.

I: “Are you secular?”

A: “No, I am not. We belong to synagogue, and I go to Hebrew school, and I go to Jewish summer camp.”

“But, you aren’t dati (Orthodox)…”

“No, we shop on Saturdays and don’t keep kosher.”

“So how is it that you aren’t secular and you also aren’t Orthodox?”

And this is when they learn that the same word has been used to describe two very different Jewish ecosystems.

Comparative Data: American & Israeli “Secular”

Before October 7, survey data in both Israel and the United States appeared, at first glance, to tell a similar story. [NOTE: I differentiate pre-10/7 because Jewish identification and identity has shifted drastically in both Israel and the US after the attack and on-going JewHate and we do not yet have reliable data sets.]

- Israel: ~42–45% identify as secular (report summary)

- United States: ~30–40% identify as secular, non-denominational, or “just Jewish” depending on question framing (report)

But those numbers collapse critical context.

Israeli Jews Who Identify as Secular: Pew and JPPI data show that many Israelis who identify as secular still participate widely in Jewish ritual, holiday observance, and collective Jewish time. In Israel, Jewish life is assumed. Most participation does not require opting in.

American Jews Who Identify as Secular: In the United States, Pew’s Jewish Americans in 2020 study shows that Jews who identify as secular or “just Jewish” still:

- attend or host Passover seders at high rates

- light Hanukkah candles

- report strong Jewish family and cultural identity

- say being Jewish matters to them, even without religious belief

And yet, because Jewish life in America is elective, these behaviors are often discounted when people hear the word secular. American Jews who use the term are often describing: distance from institutions, discomfort with denominational categories, and ambivalence about belief. They are not describing the total absence of Jewish life.

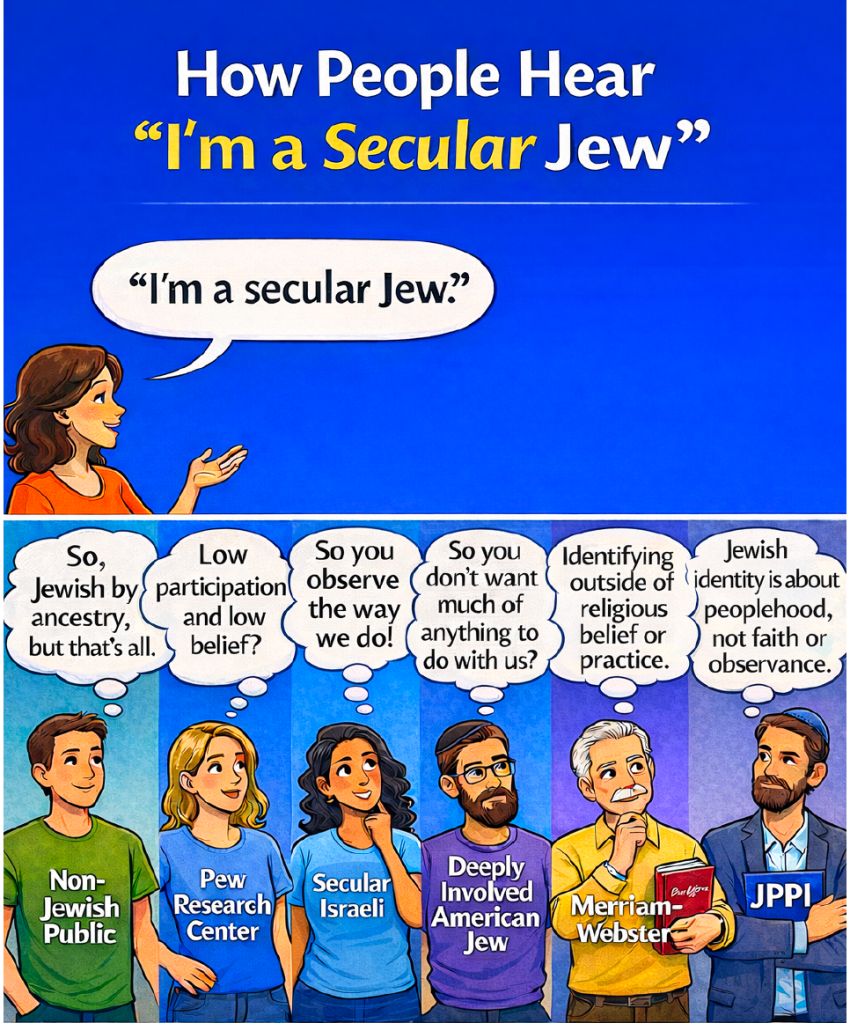

How the Same Words Are Heard Differently

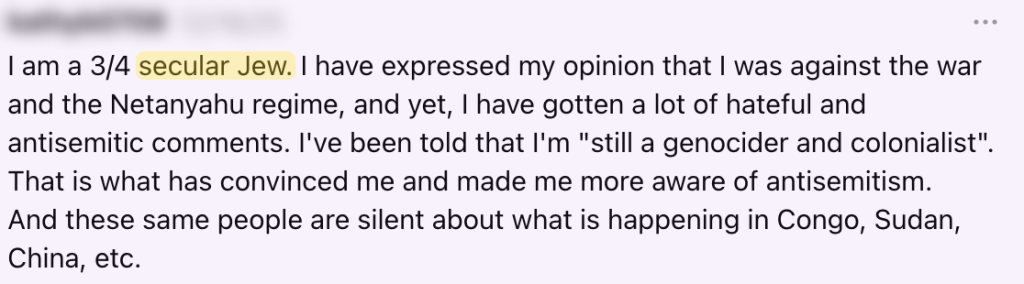

This image does not define what a secular Jew is.

It shows how many different things people hear when the same words are spoken.

- A non-Jewish listener may hear Jewish ancestry and little else.

- A researcher may hear low affiliation or belief.

- An Israeli may hear a familiar civic category.

- A deeply involved American Jew may hear rejection of shared practice.

- A dictionary may hear identity outside religion.

- A policy institute may hear peoplehood without observance.

None of these interpretations are malicious. None are fully wrong.

And none are the same thing.

But, What “Secular American Jews” Often Mean

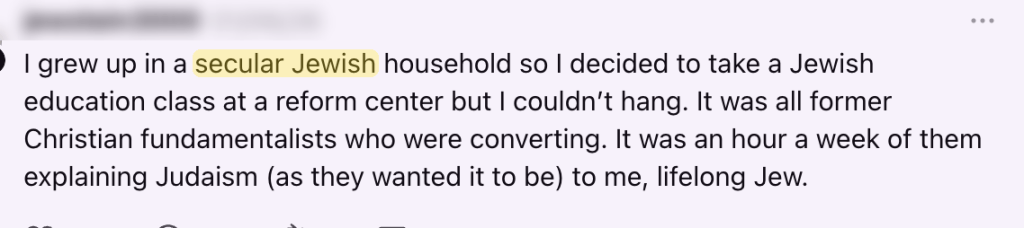

This image is not about how others interpret the term. It is about how Jews themselves often mean it.

- For some, it means a culinary and cultural memory.

- For others, values and ethics.

- For others, holidays practiced informally.

- For others, Israel as connection or experience.

- For others, peoplehood without belief.

- For others, continuity and visibility for their children.

All of these are Jewish lives. All are truthful.

None mean exactly the same thing.

When the Framework Doesn’t Fit

I personally identify as a post-denominational Jew. My relationship to Jewish life is self-directed rather than institutionally mediated, and it has been for many years.

In a 2012 blog post, I reflected on why my Jewish engagement did not neatly fit into the categories often used to measure participation in organized Jewish life. That earlier reflection provides important context for how I am thinking now about language, identity, and what people mean when they describe themselves as “secular.”

This is not me rejecting Jewish community or institutions. It is an acknowledgment that the way I live Jewishly, and the way many others do as well, does not align cleanly with the frameworks most often used to describe us.

I also want to direct you to these blogs (here, here and here) if you your thought is to use “not religious, but spiritual” and why that framing is incompatible with Jewish life.

Why the Word “Secular” Keeps Failing Us

The word secular is being asked to carry too much. It is standing in for:

- agency

- distance from authority

- discomfort with institutions

- cultural continuity

- ethical grounding

- peoplehood

- memory

- belonging

When one word has to do all that work, it stops being descriptive and starts obscuring more than it reveals.

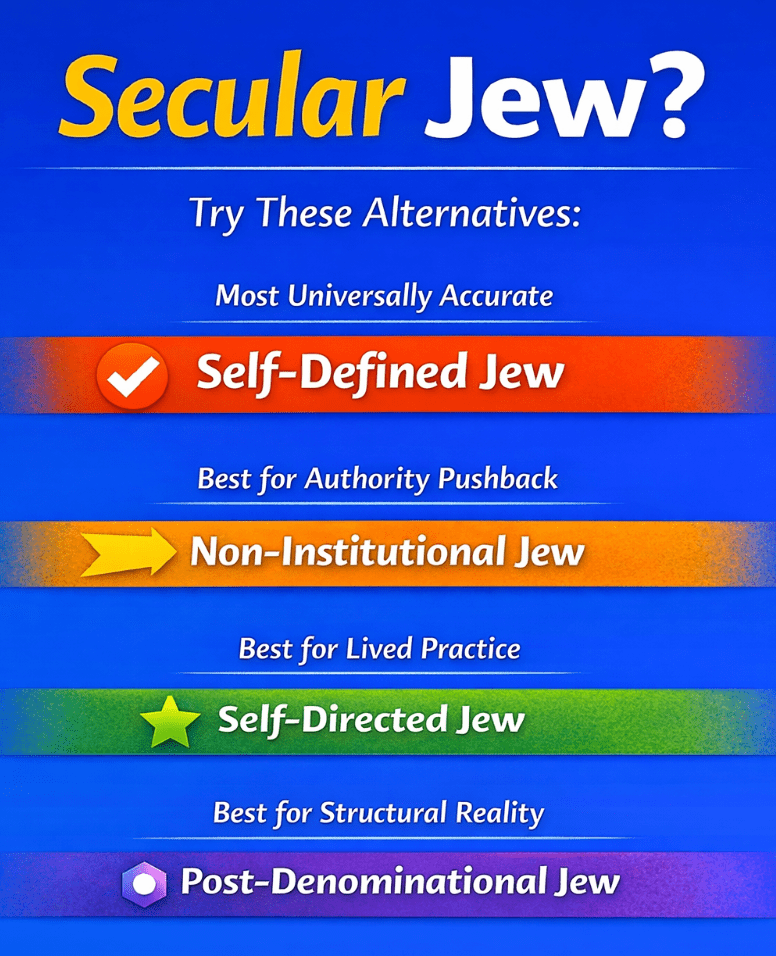

Proposing Clearer Language & Different Questions

Some alternatives travel better across contexts.

Self-defined Jew emphasizes agency.

Non-Institutional Jew centers Jewish life and identity outside of communal belonging.

Self-directed Jewish life highlights lived practice without institutional mediation.

Post-denominational Jew names a structural reality rather than disengagement.

None are perfect.

But they point toward clarity rather than absence.

However, the ultimate goal is not to replace one label with another. The goal is to slow down the assumptions we make when Jews describe themselves and ask clarifying questions like:

- What does Jewish life look like for you?

- Where does Judaism show up in your daily life?

- What feels inherited, and what feels chosen?

Ultimately, language should open conversations, not close them.

Leave a comment