When Justice Spaces Become Unsafe for Jews

This piece is being published on MLK weekend intentionally:

not because this is a moment of moral clarity,

but because it is a moment of moral strain.

Jews have long stood in public spaces alongside vulnerable communities because we recognize the terrain. Displacement. Demonization. Conditional belonging. We do not need to be taught why solidarity matters. It is written into our collective memory.

For many progressive Jews, the rupture of the past two years is not simply political. It is deeply intertwined with our sense of Jewish identity.

We did not wake up one day and abandon justice work. We woke up to find ourselves unwelcome in spaces where we had spent decades showing up, donating, marching, organizing, and building coalitions. The values that brought us there have not changed. The conditions have.

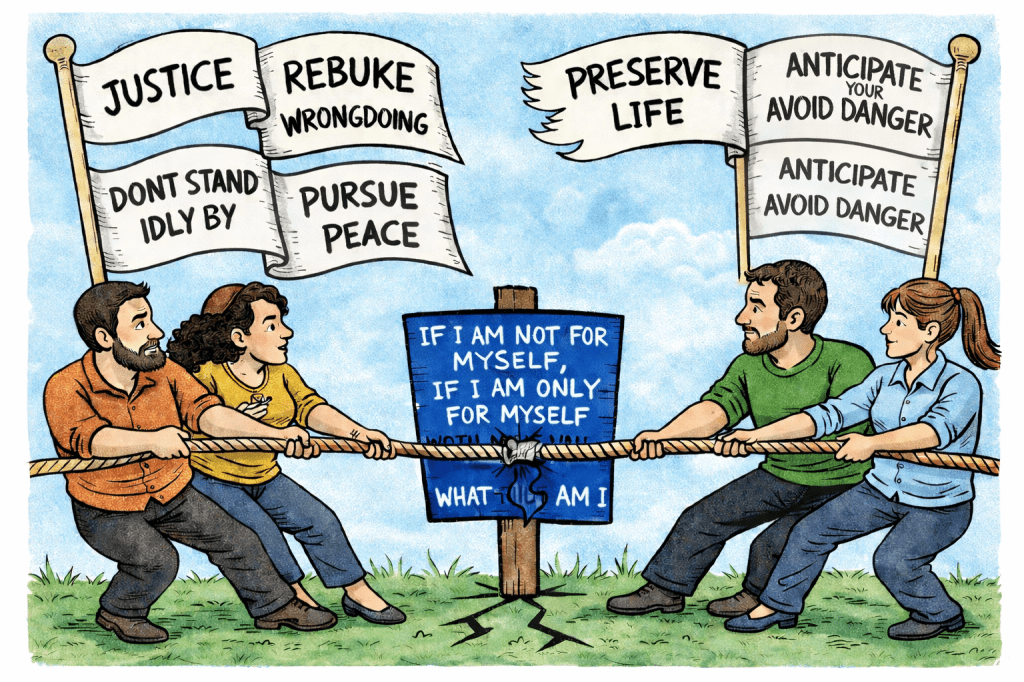

What makes this moment so destabilizing is not disagreement over policy. It is the collision of Jewish obligations that all feel binding, even when they pull us in opposite directions.

From Allyship to Alienation

Since October 7, the escalation of Jew hate has often arrived through the language of anti-Israel and anti-Zionism. While this rhetoric represents a minority within the Democratic Party, it has become disproportionately loud in certain progressive and justice oriented spaces. And, the silent majority is contributing to the noise. “The silence in deafening!”

Many Jews who previously marched for racial justice, women’s rights, immigrant dignity, and LGBTQ equality have been forced to confront a painful reality. Some of the organizations and coalitions they supported no longer treat Jewish safety, Jewish peoplehood, or Jewish trauma as compatible with their moral frameworks.

This has shown up in concrete and documented ways.

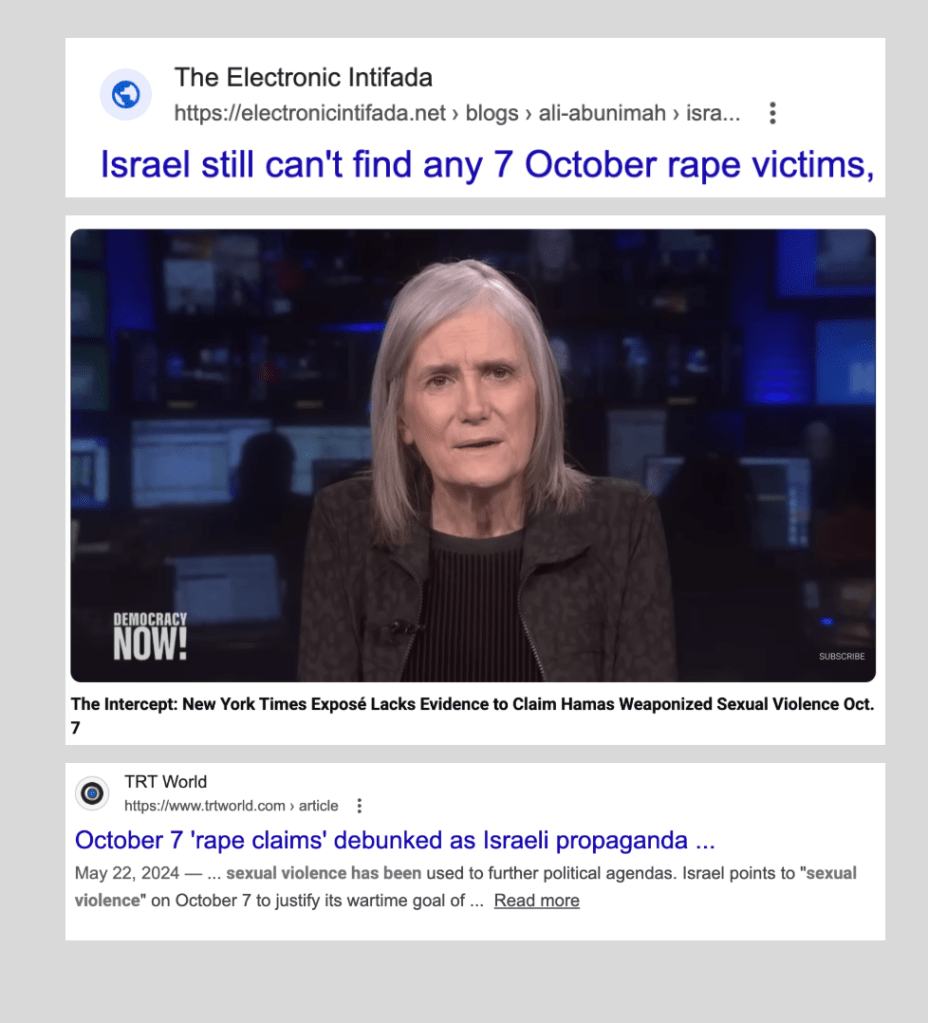

Jewish women have been told they are lying about sexual violence committed by Hamas, despite confirmed findings by the United Nations Special Representative on Sexual Violence in Conflict, which reported in March 2024 that there are reasonable grounds to believe conflict related sexual violence, including rape and gang rape, occurred during the October 7 attacks. (I suggest watching Screams Before Silence documentary.)

Even after this reporting, Jewish women’s testimony has been publicly questioned or minimized, prompting UN Women to issue a statement affirming that sexual violence against Israeli women must be acknowledged and condemned without equivocation.

Jews have been told they are not welcome at Pride events unless they renounce Israel or Zionism. Jewish LGBTQ organizations, including Keshet, alongside research from the Anti-Defamation League, have documented exclusions, litmus tests, and the singling out of Jewish symbols in Pride and queer activist spaces.

Participation in progressive coalitions has also increasingly been conditioned on rejecting Jewish self determination, a trend visible in post October 7 statements and resolutions by groups such as the Democratic Socialists of America, which frame Zionism itself as incompatible with justice work.

At protests and justice rallies, Jewish peoplehood has at times been denied outright, with Jews framed solely as a religious group rather than a people. This pattern has been analyzed by the Institute for the Study of Global Antisemitism and Policy, which identifies denial of Jewish peoplehood as a contemporary antisemitic framework within activist movements.

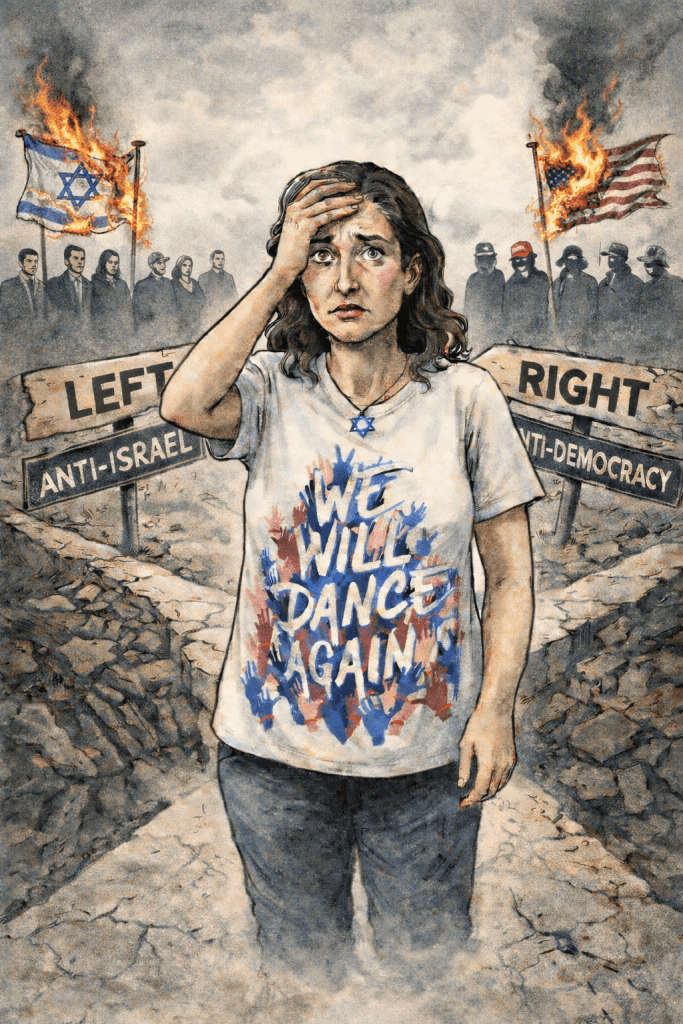

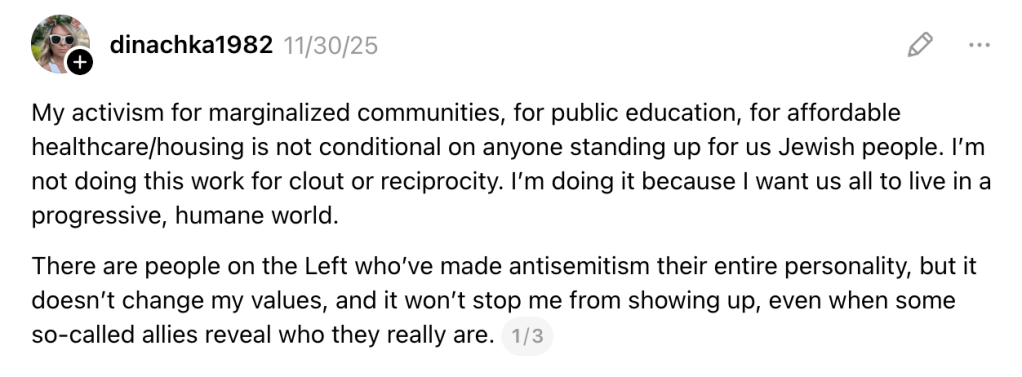

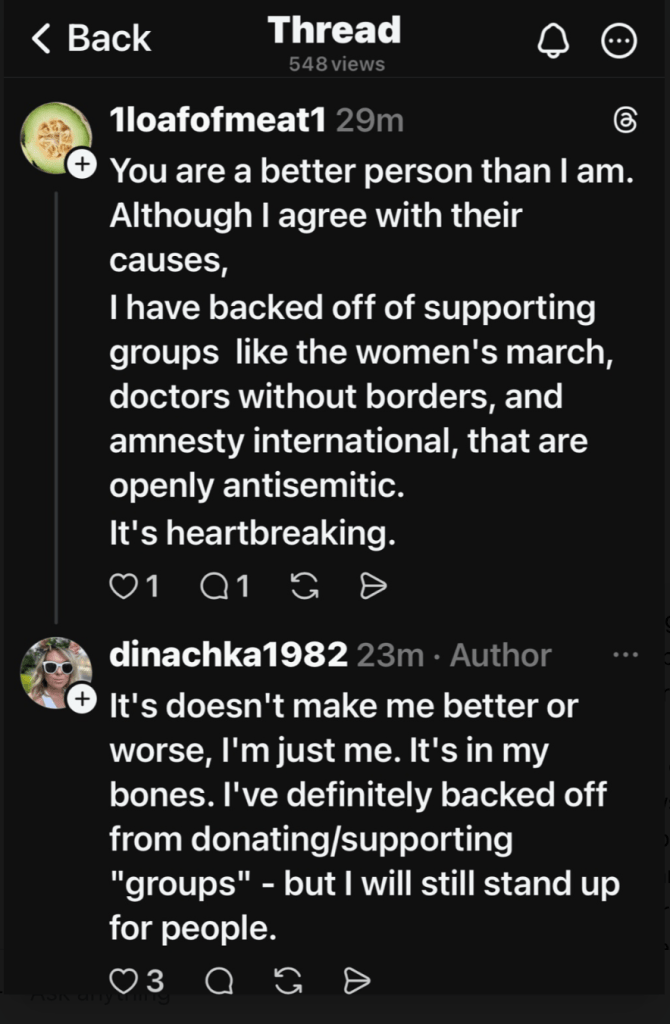

The result has not been mild discomfort. It has been emotional unsafety and, at times, physical risk. For many Jews, the issue is no longer abstract disagreement, but the lived experience of being told their pain is illegitimate, their identity conditional, and their presence negotiable. [Note: I want to acknowledge that for many Jews, like the ones depicted in the image below, they live in the intersectionality of many of these vulnerable populations alongside being Jewish, and for them, this moment is even more complicated and painful.]

I recently saw a post that accidentally captured the contradiction perfectly.

Jews are expected to be everywhere leading movements, showing up in numbers that far exceed our actual size, while simultaneously being treated as if we are nowhere at all. Invisible when we are present, suspect when we are named.

Holding that tension without allowing antisemitism to rewrite our values or erase our presence may be one of the most Jewish acts this moment demands.

When Jewish Obligations Collide

Judaism does not give us a single answer for moments like this. It gives us tension.

We are commanded not to stand idly by when our neighbor bleeds (Lo ta’amod al dam re’echa). This charge from Leviticus 19:6 has animated Jewish participation in justice movements for generations. It insists that moral responsibility requires presence, intervention, and refusal to look away when others are harmed.

At the same time, Judaism is unequivocal about preserving life. Pikuach nefesh overrides nearly every other obligation. We violate Shabbat to protect ourselves. We are instructed not to rely on miracles, not to place ourselves in foreseeable danger, not to confuse risk with righteousness.

Judaism does not sanctify self endangerment. That concern for safety is not only reactive. It is proactive.

The Torah commands us to build a parapet around our roof (Ma’akeh). A guardrail meant to prevent someone from falling. We are held responsible not only for harm we cause, but for harm we could reasonably foresee and failed to prevent. Jewish ethics does not wait for tragedy to declare danger real. It asks us to reduce risk before someone gets hurt.

In the same way a parapet anticipates danger before someone falls, stepping back from protest spaces that have become predictably unsafe can be an act of ethical foresight rather than fear. Responsibility rather than retreat.

There is also the instruction to guard ourselves very carefully via Venishmartem me’od lenafshoteichem. This is not framed as withdrawal from the world. It is framed as obligation. Caring for one’s own safety is not selfishness. It is commanded.

These values do not cancel out our commitment to justice. They coexist with it, even when they pull us in opposite directions.

We are commanded to pursue justice: Tzedek tzedek tirdof “Justice, Justice you shall pursue!” Justice is not optional, nor is it passive. But the tradition is also deeply concerned with how justice is pursued. Rabbinic commentary asks not only what outcome we seek, but whether the path itself is just. Justice pursued through humiliation, erasure, or moral coercion corrodes itself.

We are taught to pursue peace in the value Deracheha darchei noam. The ways of Torah are meant to be ways of pleasantness and peace. But peace in Jewish tradition is not silence, and it is not submission. Harmony that requires denying one’s own dignity is not sacred peace. It is coercion.

We are instructed to rebuke wrongdoing. (Hocheach tochiach et amitecha). And yet we are equally warned not to shame, not to humiliate, not to rebuke in ways that cause harm. Speaking up is an obligation. Discernment about when speech will heal and when it will inflame is also an obligation.

We are taught to see all people as created in the image of God (B’tzelem Elohim) and we are guided to mutual responsibility (Areyvut), However, we are specifically taught to protect Jews everywhere (Kol Yisrael arevim zeh bazeh). This isn’t tribalism, it is an acknowledgment that vulnerability is unevenly distributed and that survival requires particular care for one’s own community.

And then there is Hillel’s formulation, often quoted and rarely sat with long enough.

If I am not for myself, who will be for me.

If I am only for myself, what am I.

That is not a riddle with a neat solution. It is a permanent ethical instability.

So what happens when showing up in justice spaces predictably exposes Jews to harassment, intimidation, or violence. When participation requires tolerating language that threatens Jewish safety or denies Jewish peoplehood. When silence feels like betrayal and presence feels like harm.

As this piece was being finalized, two other pieces that touch on the same topic were releaed. In the first, the author published a thoughtful essay in the Times of Israel called Judaism Is Not an Enemy of Liberal Values. It argues that Judaism is not in conflict with liberal values, but is often misread or flattened by contemporary political frameworks. It echoes many of the tensions described here and is worth reading alongside this reflection. The second, The Forward published an essay examining the normalization of antisemitism within the Republican Party under the current leadership, while also arguing that core Jewish values remain deeply aligned with much of the left’s moral framework. It reinforces why many Jews feel politically unmoored, rejecting both right-wing antisemitism and the erasure of Jewish safety in some progressive spaces.

Judaism does not resolve this tension for us. It hands it to us and says act anyway. Act with humility. Act with discernment. Act without pretending this is simple. That struggle is not a failure of Jewish ethics. It is the work itself.

The Hanukkah Window, Revisited

There is a rabbinic teaching that feels unexpectedly relevant here.

The rabbis teach that we publicize the miracle of Hanukkah by placing the menorah in the window. Jewish survival is meant to be visible. But they also teach that when there is danger, the obligation does not disappear. The menorah moves inward.

The miracle is still lit.

The Judaism is still practiced.

The risk calculation changes.

That teaching does not valorize fear. It honors discernment.

For many Jews today, stepping back from certain justice spaces is not extinguishing our commitment to justice. It is moving the menorah off the windowsill when the street has become hostile.

[Note my November 2023 blog on this exact topic which includes the text.]

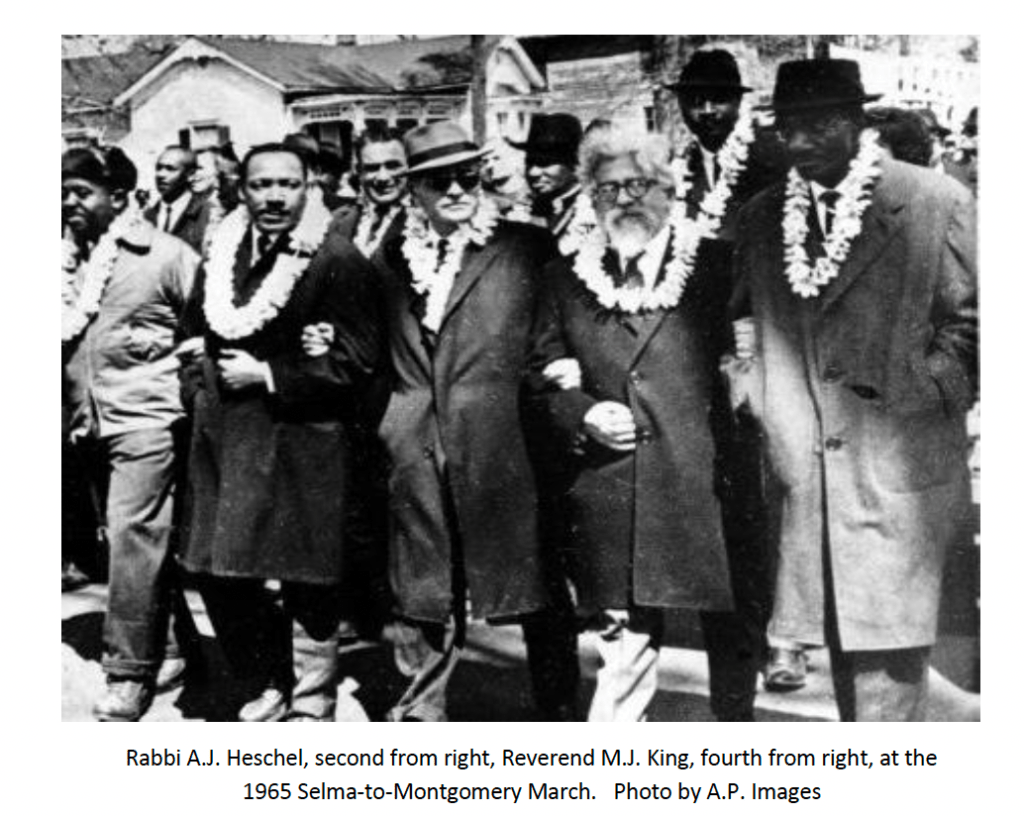

Praying With Our Feet, and Losing the Street

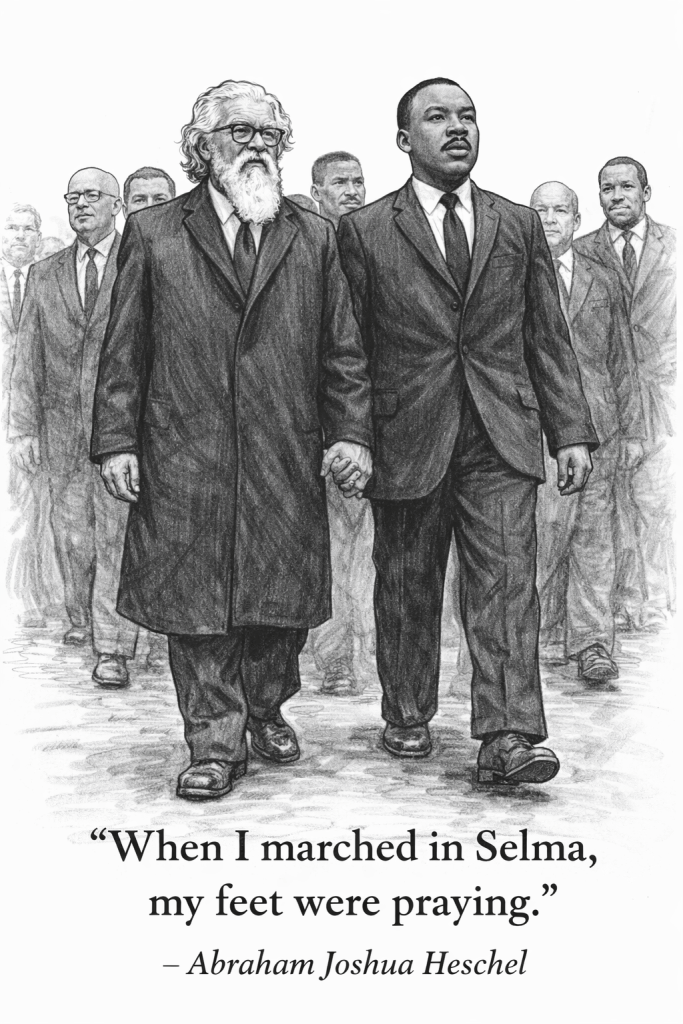

For decades, American Jews were taught that justice work was not separate from Judaism, but an expression of it.

Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel gave us language many of us inherited when he marched with Martin Luther King Jr. and said he was praying with his feet. That phrase became scaffolding for Jewish engagement in civil rights, women’s equality, immigrant justice, and LGBTQ advocacy.

Judaism lived not only in prayer books, but in public space. Which is why this moment cuts so deeply.

This post puts it more simply: caring about vulnerable people, opposing intimidation, and speaking out is not a departure from Judaism. It is deeply Jewish.

When praying with our feet becomes unsafe, it does not simply remove Jews from a coalition. It takes away a way of living Judaism.

Justice, Power, and Political Reality

One very important distinction matters.

Several people have named an important truth in recent conversations. The most extreme voices on the left largely operate in cultural and activist spaces, while the far right currently holds real institutional power. That distinction matters. It is one reason many Jews remain committed to Democratic politics even as they feel deeply alienated in progressive justice spaces.

Alienation from movements is not the same as abandonment by a political party. Conflating the two risks pushing Jews into a political no man’s land that serves no one.

This tension shows up repeatedly in Jewish conversations right now. People who feel politically homeless are not suddenly disengaged. They are often deeply engaged and deeply conflicted. They are holding more than one fear at the same time.

Judaism does not demand a single behavioral outcome in moments like this. It demands accountability, discernment, and integrity.

Some Jews step back from marches and coalitions to protect their safety and dignity.

Others continue to show up, refusing to surrender civic space or let antisemitism dictate their participation.

Both responses are real. Both are costly. Neither is lazy.

In recent months, I have seen Jews articulate this tension in many thoughtful ways. These are not caricatures or extremes. They are values driven responses to the same fracture.

Both come from the same place. A refusal to let antisemitism rewrite Jewish values.

Holding the Tension Without Disappearing

Judaism has never asked us to choose between justice and survival. It has asked us to hold them in tension, reassess when conditions change, and refuse false choices.

Sometimes praying with our feet means marching.

Sometimes it means stepping away.

Sometimes it means moving the menorah inward and lighting it anyway.

What it never means is disappearing.

Judaism does not ask us to choose between justice and survival. It asks us to hold them in tension and act anyway.

Postscript: The Pattern Beneath the Arguments

In the past few weeks, I’ve read dozens of private conversations among Jews trying to make sense of this moment. While I can’t quote them directly, the pattern is unmistakable.

Jews are naming the same fracture from different angles.

Some express deep alienation from progressive spaces that once felt like home, particularly when Jewish pain is dismissed as “just politics” or treated as a distraction from other justice claims. Others push back, insisting (correctly) that activist rhetoric is not the same as institutional power, and that abandoning democratic coalitions carries real risk.

The majority of Jews strongly oppose the actions of the current administration and fear that the alienation of Jews in the progressive spaces will lead to Jews not voting in future elections or voting third party which will lead to the country being stuck in this place.

Some reject the political right outright, seeing its pro-Israel posture as instrumental rather than protective. Others warn that far-left activism has created environments where JewHate is normalized under the guise of moral language. Many hold both truths at once and feel politically unmoored because of it.

What unites these voices is not ideology. It is grief, fear, and moral exhaustion alongside a refusal to become single-issue voters or surrender long-held commitments.

This is the cost of being small in number, historically targeted, and persistently present in justice work that was never designed with Jewish safety in mind.

Leave a comment