Religion in Public Charter Schools, and

Why We Shouldn’t Push for Exception

I have been thinking a great deal about this new article from eJewishPhilanthropy, which examines how Oklahoma’s Jewish community is pushing back against a proposed shift in a Hebrew charter school model.

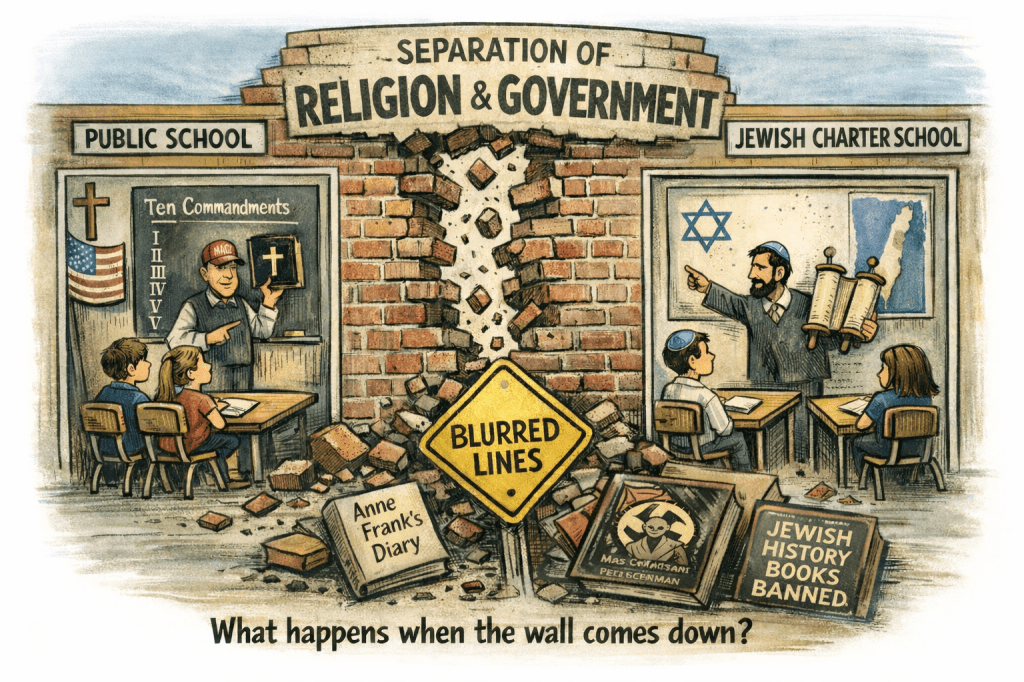

Years ago, I was invited to sit on an exploratory committee examining the possibility of Hebrew language charter schools in the Atlanta area. I entered that work as a firm supporter of the separation of religion and government. That position included opposition to religious language on public documents, religious invocations in legislative bodies, and any blurring of constitutional boundaries that protect both religious freedom and pluralistic democracy.

Because of that commitment, we went deep. We studied how a Hebrew language immersion charter school could exist fully within public education while remaining constitutionally sound. That meant language acquisition rooted in culture, history, geography, literature, and some Israel education, without religious instruction, worship, or endorsement.

That distinction matters.

What appears to be happening in Oklahoma crosses that line, and it does so at a particularly dangerous national moment. We are living through an era in which elected officials openly assert that the United States is a Christian country and suggest that those who are not Christian are suspect or lesser. These statements are not fringe. They are being made by sitting lawmakers and amplified in mainstream political discourse.

Against that backdrop, many of us had a visceral reaction when an Oklahoma school district announced the purchase of thousands of Trump Bibles so that a Bible could be placed in every classroom. That reaction was not partisan. It was not JUST constitutional. It was a reaction to a threat to religious freedom — a threat to OUR religious freedom. That reaction reflected an anger that taxpayer dollars were being used for religious intrusion into public education.

This is no different.

Once religious instruction enters public education, accreditation does not protect democracy. The First Amendment is meant to. But constitutional protections are not self executing. They rely on enforcement, litigation, and political will, all of which can take years to unfold, if they unfold at all. Even when violations are eventually challenged, appeals can drag on for years. During that time, students are taught, normalized, and shaped by content that never should have entered public education in the first place.

This is not only about the Ten Commandments or symbolic religion in classrooms. It is about whether our tax dollars can be used for religious indoctrination at all. Once public funds are permitted to support religious instruction, whether Christian, Muslim, Jewish, or otherwise, we lose one of the core safeguards of the First Amendment. That amendment was designed to protect both freedom of religion and freedom from religion, precisely because minority communities cannot rely on majority restraint.

We already know that in some private religious day schools, particularly those tied to extremist outliers, students are exposed to antisemitic material, Holocaust distortion, or ideologically driven hostility toward Jews. Oversight, via accreditation, in those settings is uneven and slow. If similar ideological drift occurs in public charter schools, the stakes are far higher. Taxpayer funds are involved. Students cannot easily opt out. And precedent is created.

Book censorship further exposes how fragile these protections are. Across the United States, school districts have banned or restricted books that are foundational to Jewish history, Holocaust education, and broader human rights literacy. The Diary of Anne Frank has been repeatedly challenged, removed, or placed behind parental permission requirements, often under the guise of protecting students from discomfort.

Other frequently banned or challenged works include Maus by Art Spiegelman, Night by Elie Wiesel, and educational resources from the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, all of which are central to understanding antisemitism, genocide, and Jewish history.

Book bans do not operate in isolation. The same political battles that restrict the teaching of Black history under the banner of opposing so-called CRT demonstrate how easily state and district authorities can intervene to control historical narratives. When governments decide which histories are acceptable to teach and which are too uncomfortable or politically inconvenient, minority narratives become conditional. Jewish immigration history, antisemitism, refugee exclusion, and Israel are all vulnerable to distortion or erasure in that environment.

So the question must be asked plainly. What happens when a Jewish charter school exists within a district or state system that bans or restricts the very literature and historical frameworks that tell our story truthfully? What protections exist when political ideology, not pedagogy, determines what can be taught?

At that point, we lose our voice. We lose the moral and legal standing to say this is not acceptable. We cannot credibly oppose Christian nationalist efforts to embed religion into public education if we are willing to blur those same boundaries ourselves. If we are disturbed by Bibles in every classroom, we should be equally disturbed when publicly funded Jewish schools drift toward religious instruction.

Hebrew charter schools work because they are grounded in language immersion, not religion. Once that line erodes, the entire model becomes vulnerable, along with the constitutional protections minority communities depend on.

This is not just a Jewish issue.

It is a constitutional issue.

It is a pluralism issue.

It is a democratic survival issue.

Clear boundaries are not a rejection of identity. They are what make shared civic life possible. Especially now, we cannot afford to forget that.

Leave a comment