A Grandfather I Never Met, and the Legacy I Inherited

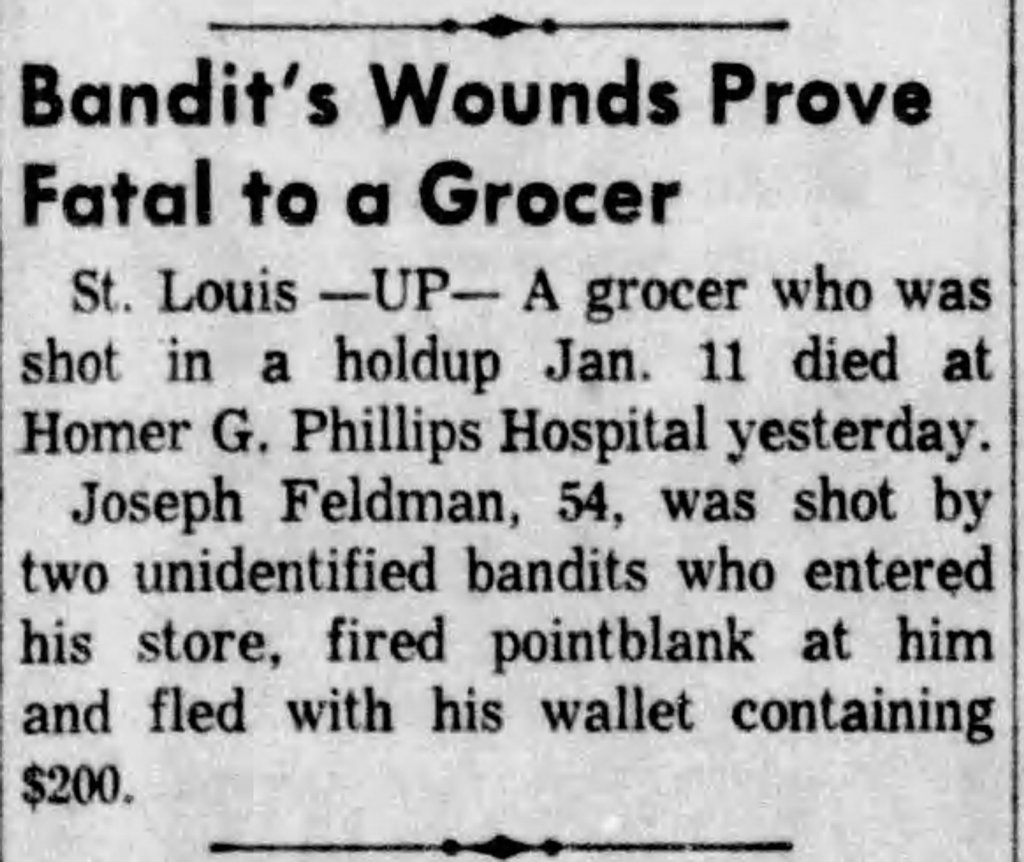

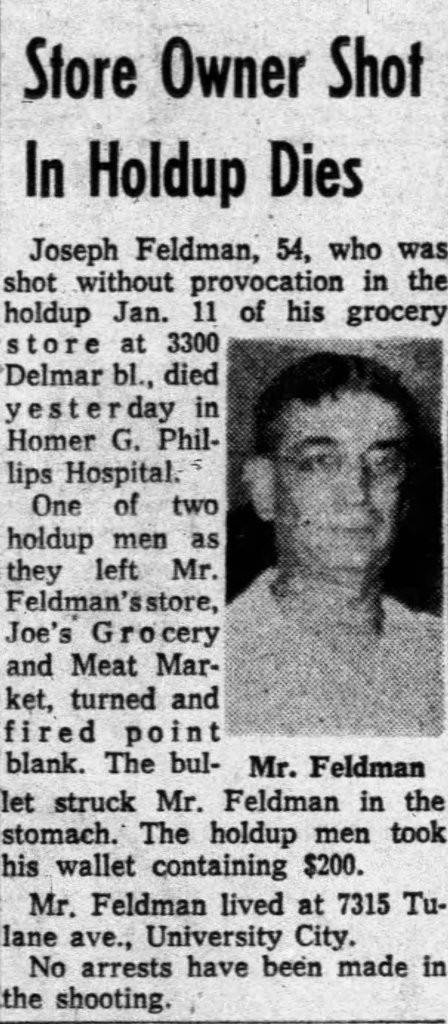

Today, January 29, 2026, is my maternal grandfather’s 68th English yahrtzeit.

My maternal grandfather was murdered when my mother was thirteen years old. I never met him. I know him through stories, newspaper clippings, and the quiet rules that shaped our home.

We were not allowed toy guns. Even water guns made my mother uncomfortable. Guns were not neutral objects in our family. They were instruments that had taken a life and permanently altered a child’s future. This is inherited trauma, yes, but it is also inherited moral clarity. Guns were not abstract to us. They were not political symbols. They were not theoretical safeguards. They were a source of irreversible harm.

So, when I see Facebook posts like these, I have a very strong visceral reaction: both because a Jewish person is asking about gun purchase, but my discomfort is reinforced by the asking about a Jewish-owned gun store. (Transparency note: a cousin of my father’s did own a gun store for many years and after he passed, his brother took some of those weapons as inventory for his coin and pawn store.)

What Happens When I Teach The Jewish Views on Guns

For many years, I have taught a lesson called Taking Aim at Gun Control to middle schoolers, high schoolers, college students, and adults. I always begin the same way by asking people to share their stories. Who has experienced gun violence or has had a close family or friend who has?

Almost every hand goes up. And then they begin to share: a stray bullet entered a hunting cabin and struck a cousin; an older sibling was mugged at gun point while club-hopping in college; a friend took their own life with a parent’s unsecured gun; a dear friend from camp survived a school shooting (or didn’t).

Regardless of their (or their parents’) personal politics, these teens have some clarity. They have grown up inside lockdowns, drills, and threat assessments. They are not theorizing risk. They are living inside it.

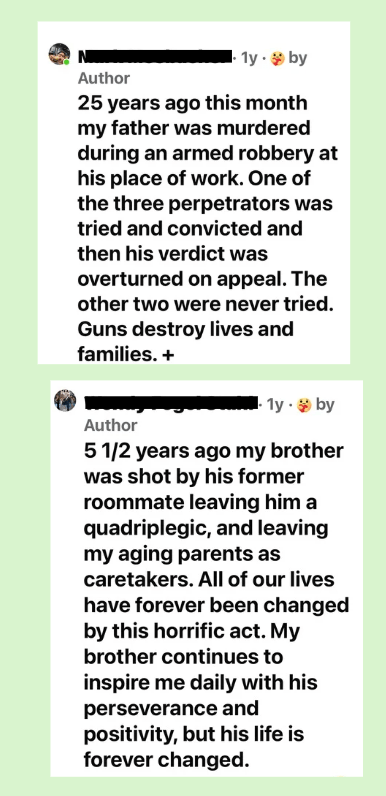

Adults share stories about parents murdered, a sibling permanently disabled as a quadriplegic after a roommate argument escalated, partners held at gunpoint, an in-law shot and seriously wounded during a mass attack event, a friend taking their own life with a gun, neighborhoods forever altered after families wiped out from murder-suicide. (I asked a few of folks to share their stories with me on Facebook, see images to left.) Even in rooms of relatively privileged learners, gun violence is not distant. It is personal.

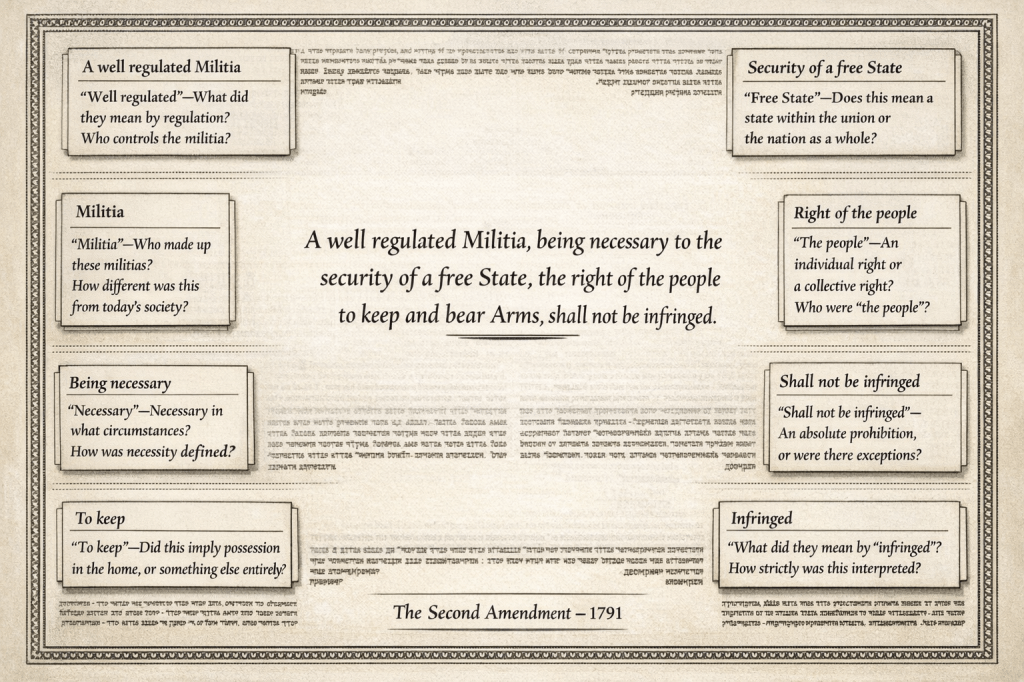

After we have an open, often emotional, sharing session, I ask learners to engage in a different kind of “text” study: one with the Second Amendment. I treated the Second Amendment the way I would treat a Jewish text. Slowly. Carefully. Examining each word with attention to language, context, and interpretive responsibility. The debate is not whether the Second Amendment allows civilian gun ownership. It clearly does. The deeper question is how Americans interpret it, what weight we assign to its words, and what moral claims we attach to it.

When Jews encounter a foundational text, we do not isolate a single clause and absolutize it. We place it in conversation. We ask what problem it was responding to. We ask what assumptions it makes about power, responsibility, and human behavior. We ask what guardrails are implied, even if they are not explicitly named.

One takeaway when my learners engage in this process, reading the Second Amendment as Jews read Torah, is to wrestle with the term “regulated.” Some conclude that it is an obligation for safety and boundaries around unlawfulness. This approach does not erase constitutional rights. It reframes them. It insists that freedom without restraint is not liberty. It is negligence.

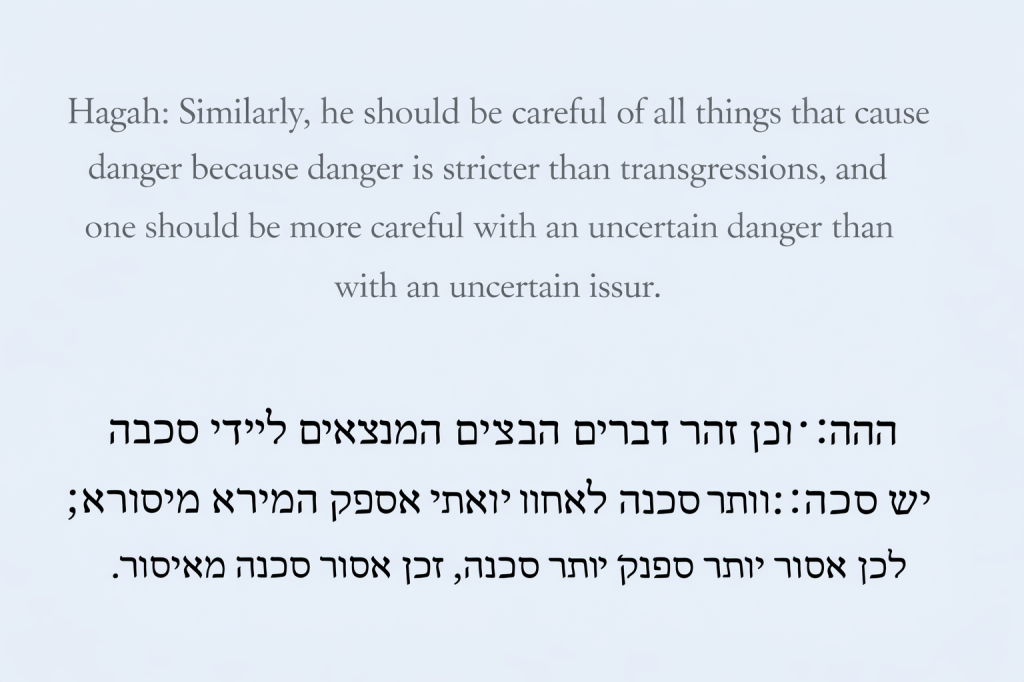

After this unconventional exploration, I lead them through an encounter with numerous Jewish texts. Jewish wisdom insists that lived danger matters. We do not wait for tragedy to validate caution. We act when risk is foreseeable, not only when harm has already occurred. Jewish law also recognizes the right to take a life if someone is actively pursuing yours. That distinction matters and deserves careful investigation. (See section below for closer examination of some of the texts.)

What emerges from this multi-layered learning is not a blanket endorsement of weapons nor a blanket condemnation. It is a framework of restraint, accountability, and deep discomfort with unnecessary risk.

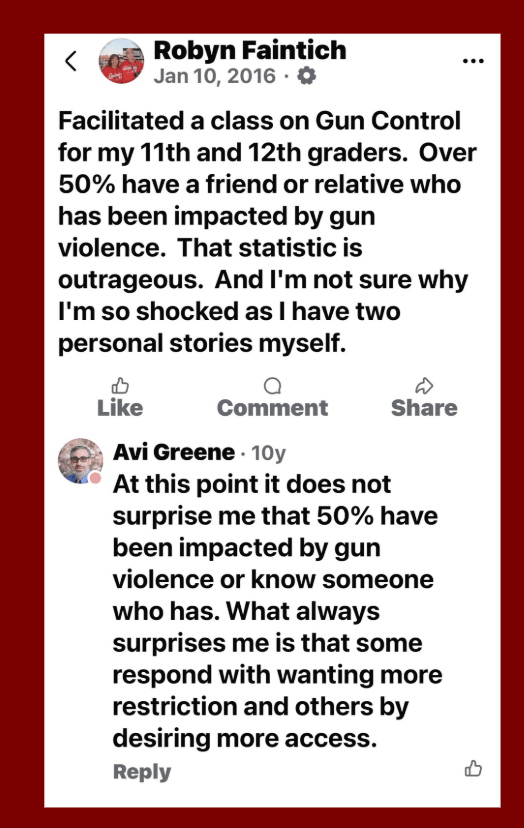

Many years ago, I shared on Facebook a summary of one of these classes, and an old friend (who is also now a rabbi and day school educator) offered a framing that has stayed with me because it explains so much of what we are seeing now: When people encounter gun violence, some respond by wanting fewer guns. Others respond by wanting more access. Same exposure. Same fear. Opposite instincts.

This is the fracture running through Jewish spaces today.

The Questions Being Asked in Jewish Spaces Right Now

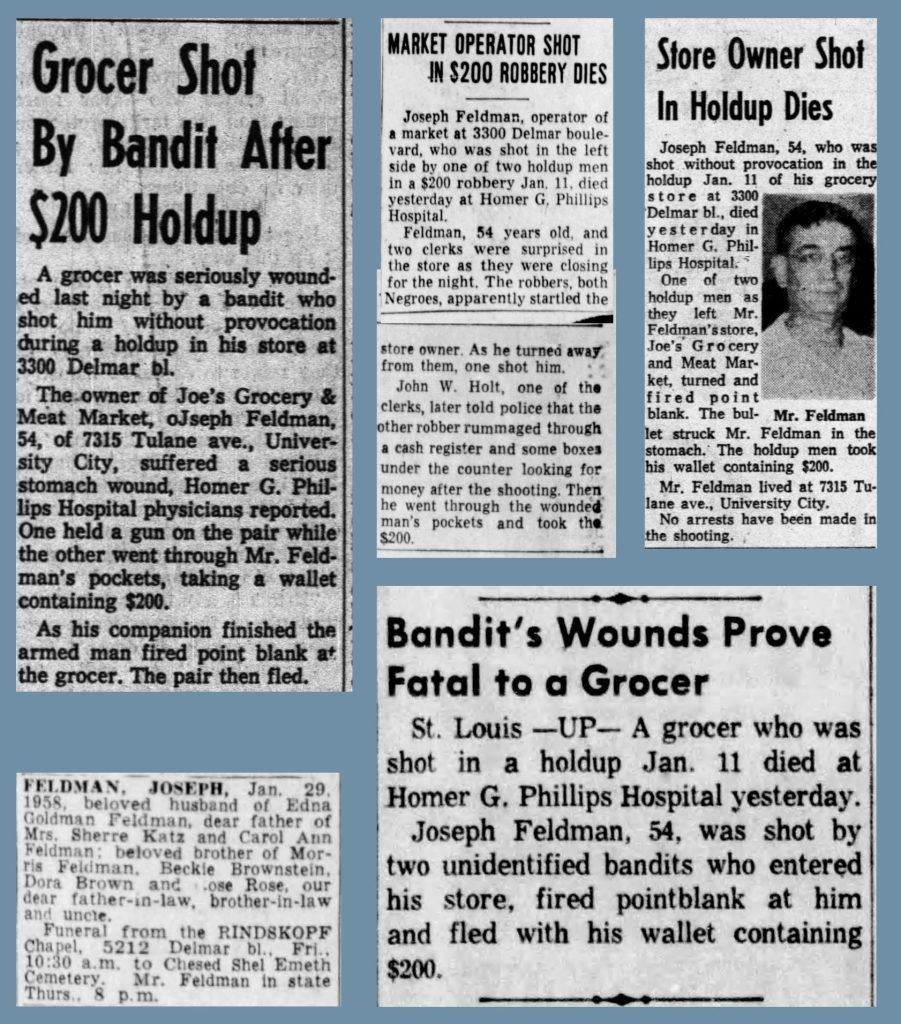

We are living in a moment of real danger. Jews have been murdered in synagogues, community centers, museums, and public spaces. JewHate (aka antisemitism) is no longer theoretical nor hidden in small, insulated rural communities. It is loud, visible, and violent. And increasingly, within Jewish communal discourse, that fear is producing a particular conclusion. Jews need guns.

“It’s open hunting season on Jews,” Lizzy Savetsky wrote in a Facebook post to her nearly 500,000 followers. “Nobody is coming to save us. Wake up. Arm up. Responsibly. This is not about being cool or tough; it’s about survival.”

The framing is often emotional, rooted in fear, trauma, and memory. Those emotions deserve to be acknowledged. In the last few years, more gun clubs and volunteer Jewish security forces have emerged or become more public in their outreach. Training programs frame firearms as communal protection. Some voices argue that Jewish history demands self-defense at all costs. Here is a list of some of the clubs, security forces, advocacy groups and folks privately training Jews:

In response to all of this, there have been a number of articles and opinion pieces appearing in Jewish news outlets.

- Hadassah Magazine: The Era of the Jewish Gun Club

- Jewish Journal: Jews Must Arm Themselves

- Jewish Journal: Jews and Guns: Time for a Reckoning?

In one of these articles, the author David Bernstein writes, “as antisemitism rises and threats to Jewish safety grow, can we really afford to cling to that hostility—or the smugness that comes with it? Should more Jews be willing to learn how to use, and perhaps even own, firearms? Is it time to end the taboo? Perhaps it’s time to make amends not only with guns, but also with the millions of our fellow Americans who carry them.”

When “Responsible” Guns Create New Risks in Jewish Spaces

Some of the most troubling stories I have heard about guns do not come from mass shootings or national headlines. They come from inside Jewish communal life itself.

A few years after I left Texas, I learned of an incident in which a man attending synagogue stood up during services and a gun fell out of his pants. It discharged. His daughter was shot in the foot. This did not happen in a chaotic public space. It happened inside a house of worship, during prayer, because a congregant brought a firearm where it did not belong.

A professional in another Jewish community once shared that their synagogue had a clear policy: no one was permitted to carry a gun in the building unless they were part of the official security team. One congregant repeatedly pushed back against this rule, insisting he should be allowed to carry. Leadership said no. On the High Holidays, he approached synagogue staff in distress. He had brought his gun anyway and casually stored it in his tallit bag. He could no longer find the bag. For a period of time, there was an unsecured firearm somewhere in the synagogue. Nothing catastrophic happened. That is not the point. The point is how close it came. Imagine if a child had picked up that bag. Imagine if someone unfamiliar with firearms had opened it. Imagine if panic had set in.

These are not stories about malice. They are stories about human fallibility. They illustrate exactly why Jewish law treats danger as more severe than transgression and why intention is never sufficient protection.

This is also why Jewish security professionals, including the Secure Community Network (see below), warn against informal or individual gun carrying in synagogues. Structure matters. Clear authority matters. Accountability matters. Good intentions do not prevent accidents. Rules do.

Jewish Security Professionals Are Warning Against Unregulated Armed Spaces

As guns have become more visible in Jewish communal life, Jewish security professionals have begun urging caution.

The Secure Community Network (SCN), the official homeland security organization for the Jewish community in North America, has called for stronger regulation, not wider individual gun carrying, in synagogues. SCN developed a White Paper report making recommendations including formal security structures, training, clear authority, and coordination with law enforcement. It explicitly warns against informal or individual firearm carrying in synagogue spaces. This matters. It tells us that expertise, not fear, points toward restraint.

Subsequently, the JTA wrote an article about the increase in Jewish gun clubs and conducted a bit of a compare/contrast with the SCN report. The article highlights the tension between grassroots gun acquisition and professional security guidance within Jewish communities.

What Jewish Law Actually Requires of Us: Common Sense Gun Control Recommendations through Jewish Text

So, with all of this, how do I reconcile the need for keeping our communities, and ourselves, safe (particularly from JewHate), with my inherited family trauma? How do I reconcile individual desires to protect our institutions with the security network advising against it? When I am wrestling with something this significant, more often than not, I turn to Jewish wisdom to help me shape my thinking.

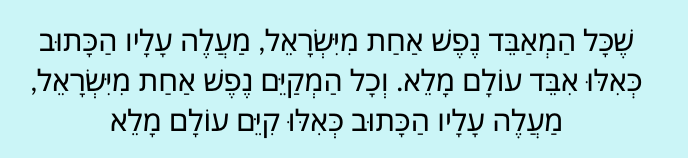

The most important piece of Jewish wisdom that frames this debate is based in the obligation to save a life: pikuach nefesh. It is situated first from Leviticus 18:5 “You shall keep My laws and My rules, by the pursuit of which humans shall live: I am GOD.” But this obligation is more well-known from this text from Mishnah Sanhedrin.

Jewish law demands we preserve life, even if it means violating other mitzvot.

Safety Measures

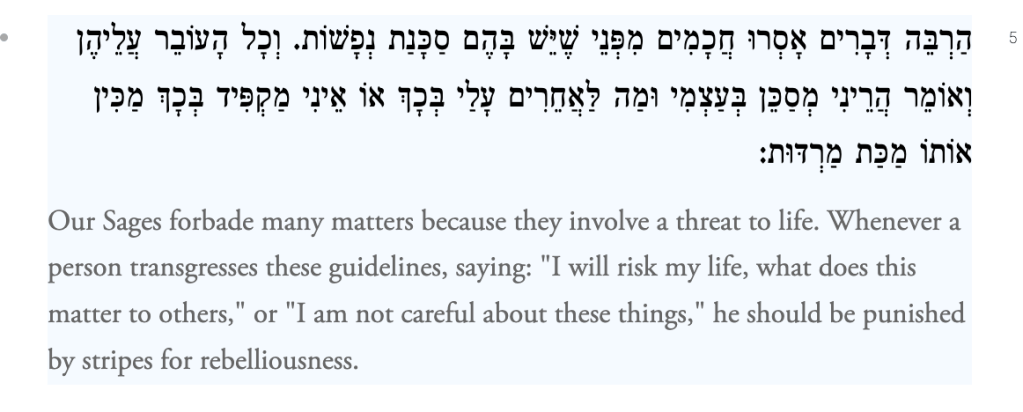

Jewish law does not treat danger as a private choice and one who does so is punished. In addition, risk imposed on others is a moral failure. Jewish law does not ask whether danger is predictable, it asks whether it is preventable.

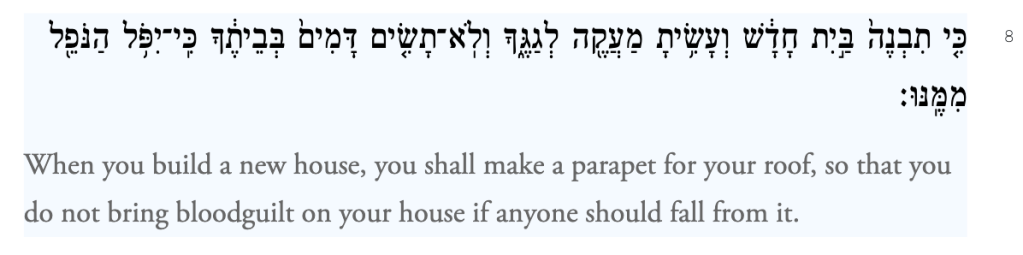

We are also obligated to prevent a foreseeable accident that with a slight alternation, can prevent it. A parapet is a proactive safety measure. It exists because accidents are predictable. Guns, like rooftops, require barriers.

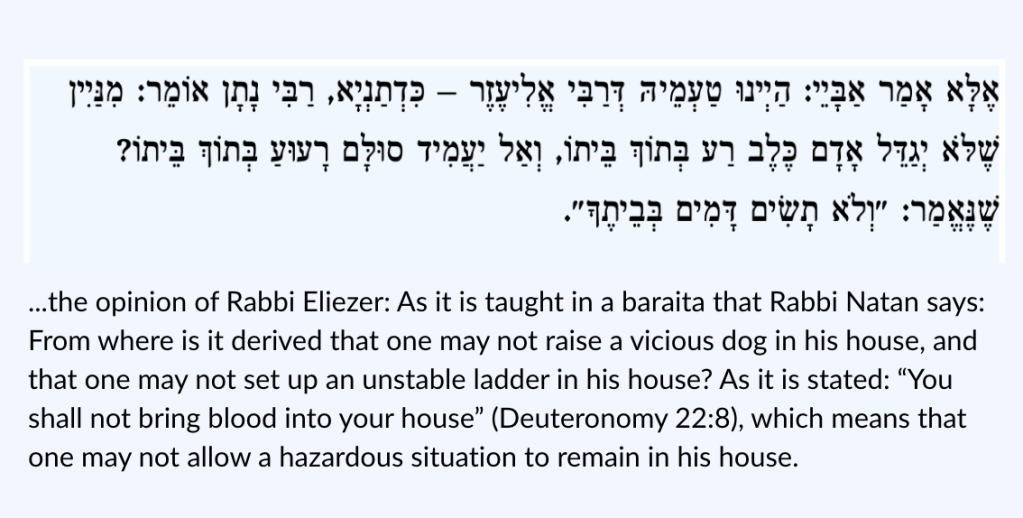

In addition to building safe guards, we must also not bring into our homes items we know that can be dangerous, nor can we use items that we know to be unsafe.

This collection of texts frames common sense gun laws around lock boxes with fingerprint technology, weapon triggers with similar biometric securities, and gun safety training for everyone in a home.

Training and Licensing

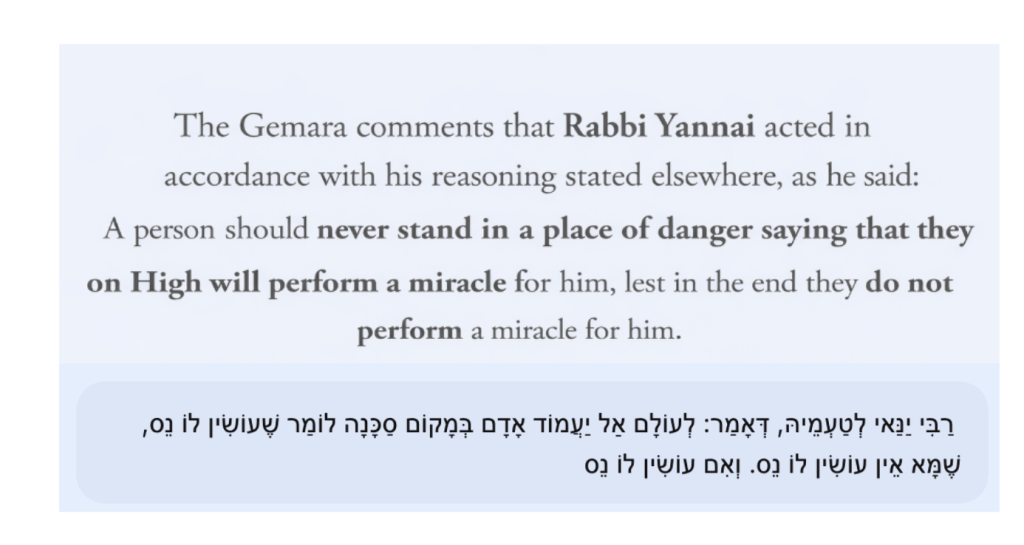

One interpretation of this text, is that we know handling a weapon is dangerous. And to ignore that danger is irresponsible. To “hope for a miracle” that you won’t be hurt while in the possession of a gun is risking that the miracle will not come. Therefore, anyone who is to own a gun needs to be required to engage in serious training.

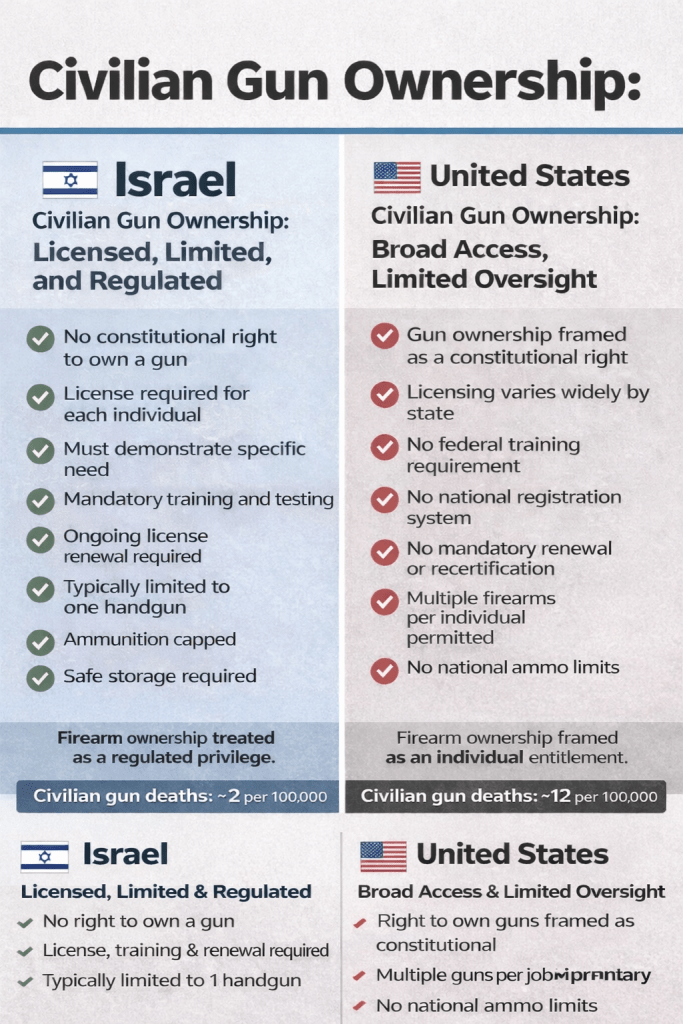

In the United States, operating a car is treated as a regulated public responsibility, while owning a gun is often framed as an individual entitlement, even though firearms are designed to kill and cars are not.

You cannot legally drive a car without passing a written test, demonstrating practical competence behind the wheel, holding a license that must be renewed, registering the vehicle with the state, and carrying mandatory insurance. If a driver behaves recklessly, loses capacity, or poses a danger to others, their license can be suspended or revoked. There is no constitutional right to drive, yet society broadly accepts these safeguards because cars can cause serious harm when misused.

By contrast, in many U.S. states a person can purchase and carry a firearm without any mandatory training, without demonstrating practical competency, without an insurance requirement, without a national registration system, and without regular recertification. Firearms, which are explicitly designed to inflict lethal harm, are often subject to fewer safeguards than cars.

This leads to an unavoidable conclusion. If we accept licensing, testing, insurance, registration, and renewal as reasonable protections for operating a vehicle, there is no coherent ethical argument for rejecting those same safeguards for weapons designed to kill. The Jewish ethical argument demands it.

Do Not Arm Those Who Should Not Be Armed

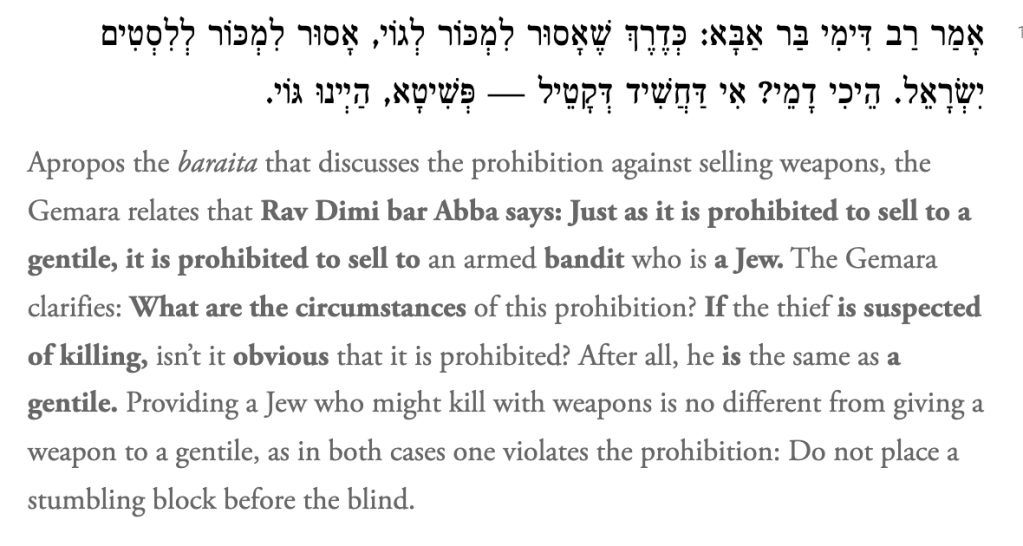

One of the clearest Jewish texts on weapons is also one of the most overlooked. The entire selection of Talmud, Avodah Zarah 15b:10 is a fascinating debate on who can buy and sell weapons and to whom they shouldn’t be sold to. But the most important part is specifically about not selling a weapon to a criminal:

This text forms a direct foundation for background checks, red flag laws, and firearm access restrictions. Jewish law does not wait for violence to occur. It acts at the point of foreseeable risk.

Transparency Matters

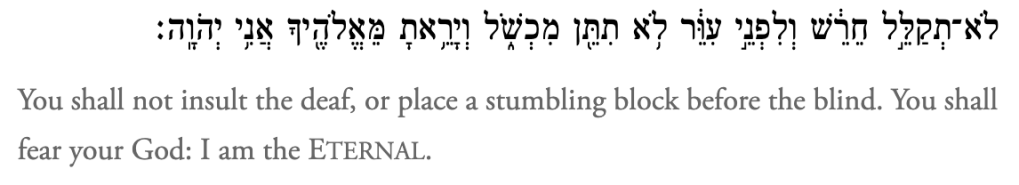

The last line in Talmud Avodah Zarah 15b:10 says, “Do not place a stumbling block before the blind.” But this is also found in Leviticus 19:14.

In a modern context, this text raises uncomfortable questions about secrecy. If firearms increase risk, then concealed ownership can create harm even without intent. This is where the case for publicly searchable gun ownership databases emerges and the inability to purchase a weapon without being in the database. Parents deserve to know whether firearms are present before sending a child to a home. People deserve to know if their co-worker has a conceal-carry license and may potentially be armed in the cubicle next to them. First responders (besides police) deserve to know if they are possibly entering a home where a gun is on the premises. Communities deserve transparency when danger exists.

So, with exploring the Jewish wisdom, what I now accept is strict licensing, mandatory training, recertification, insurance, registration, safe storage, and technological safeguards like biometric trigger locks.

This is not compromise for comfort. It is compromise for harm reduction.

[For a complete discussion guide, you can download this sheet from Sefaria.

It is based on the text study I have led for years and later was adapted for client work.]

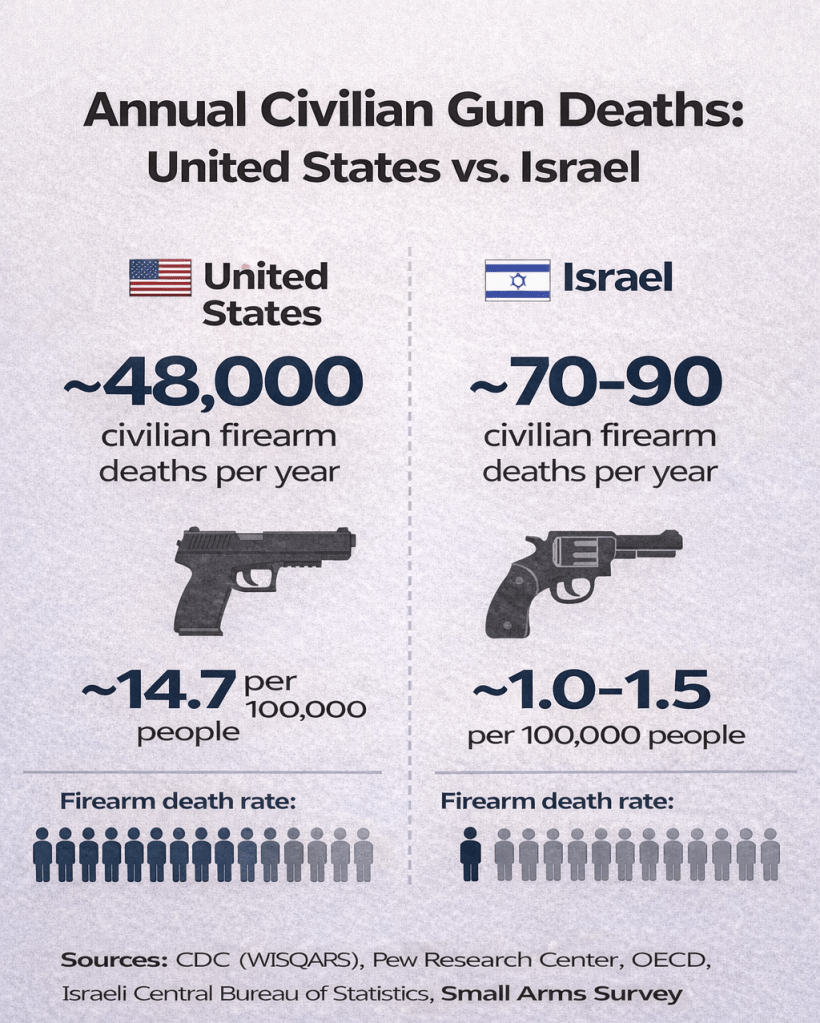

Israel Is Not the Argument People Think It Is

Israel is often invoked as proof that an armed society is a safer one. “Despite the modern American Jewish aversion to arms, it has not always been so, and Israeli Jews certainly understand the value of arms,” JFPO website. This comparison is flawed.

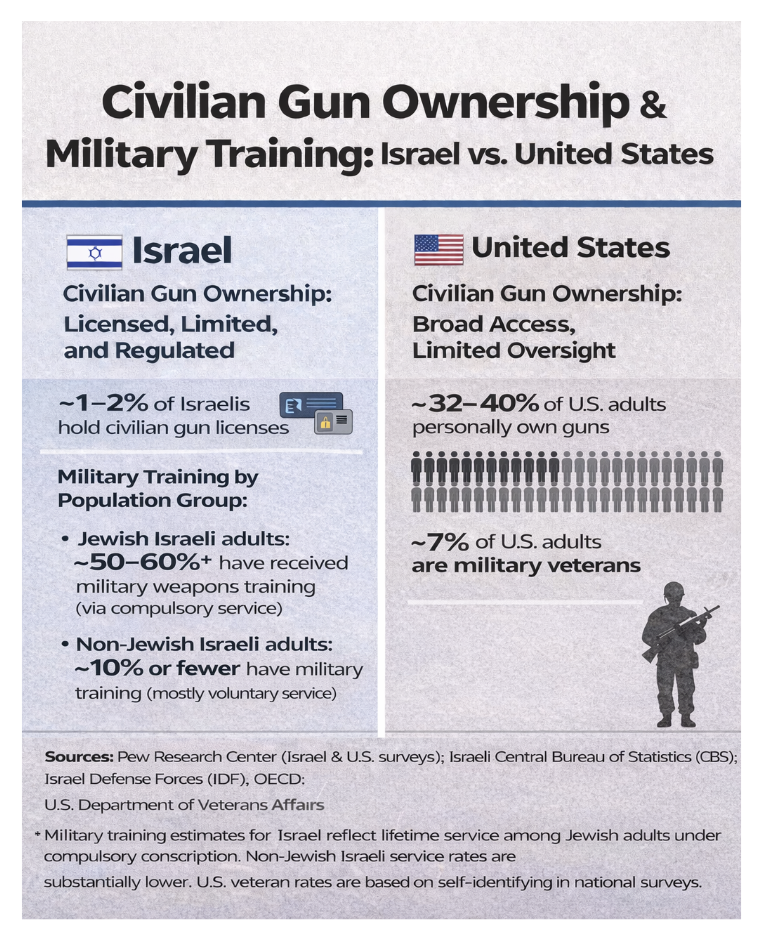

Israel does not have broad civilian gun ownership. Civilian firearm licenses are rare, tightly controlled, and subject to renewal, training, and justification.

While many Jewish Israeli adults (and some non-Jews) have military weapons training due to compulsory service, very few hold private gun licenses. Training does not equal entitlement. This distinction is critical.

The United States experiences tens of thousands of civilian gun deaths annually. Israel’s numbers are dramatically lower, even accounting for regional conflict.

accidental firearm deaths.

The difference is not cultural temperament. It is policy. A policy American Jews should look to in shaping their views on gun laws.

But, our hunting guns …

Discussions about guns often pivot to hunting, framed as tradition, recreation, or responsible use. It is important to name that Jewish ethics approaches this very differently than American gun culture often does.

Jewish law permits the taking of animal life only under strict moral constraints. The principle of tza’ar ba’alei chayyim, the prohibition against causing unnecessary suffering to animals, underlies the laws of kashrut and requires that even permitted killing minimize pain and avoid cruelty. The Torah allows the consumption of meat, but it does not celebrate killing, and it certainly does not sanctify it for sport.

Maimonides makes the ethical concern explicit in the Guide for the Perplexed III:17,24. He explains that cruelty to animals is not morally neutral because it shapes the moral character of human beings. Unnecessary killing cultivates callousness. Power exercised without restraint deforms the soul of the one who wields it. He is explicit: “We should not kill animals for the purpose of practising cruelty, or for the purpose of play.”

For this reason, killing for recreation does not align with Jewish values of humility and self-limitation. Even when animals are taken for food, Jewish law surrounds the act with restrictions, blessings, and discipline. Hunting for sport strips those safeguards away and reframes killing as entertainment.

This matters in a broader conversation about guns. When weapons are normalized through recreation, training shifts from responsibility to enjoyment. The object designed to kill becomes a source of pleasure rather than a last resort. Jewish tradition resists that shift. It demands that lethal force remain tragic, constrained, and morally fraught, never casual and certainly never celebrated.

Praying With My Feet

For me, this well-known sentiment by Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel, isn’t a part of history, but an embodied value I strive to enact. Often.

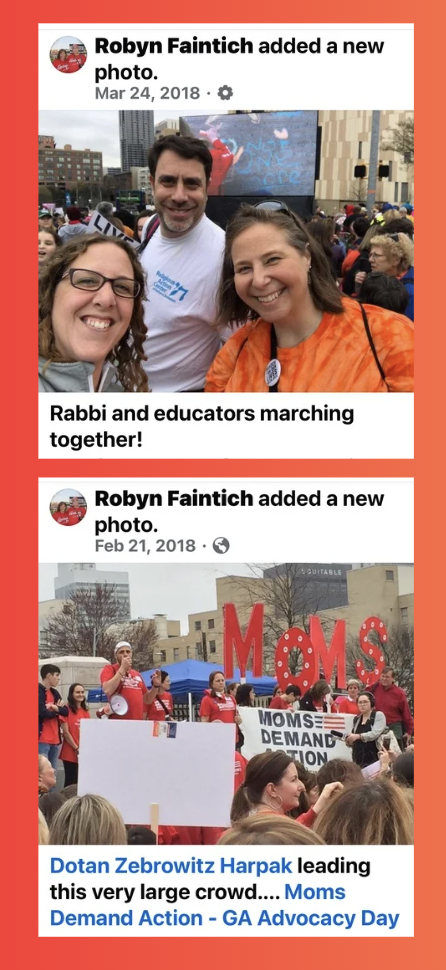

As it relates to gun control advocacy in our country, I am a monthly supporter of Everytown for Gun Safety. I have participated in March for Our Lives and other gun control actions over the years. I have shown up not because it was politically fashionable, but because gun violence has shaped my life.

In 2024, I attended an event where Gabby Giffords and Senator Mark Kelly spoke about gun violence prevention, public policy, and the moral urgency of action. I drove an hour to be in the room. This was not a rally. It was a sober, difficult conversation about what it means to persist after trauma and to use our voices to impact societal change.

What struck me most was not the policy language, but the cost. Every word Gabby Giffords spoke required effort. Every step she took was deliberate. And still, she continues. That persistence matters.

After the event, I shared my own story. I talked about my grandfather’s murder. I talked about how gun violence shaped my mother’s childhood and, by extension, my own life. I talked about friends lost to suicide by gun and friends who have survived armed confrontations that changed them permanently.

I include this not to center myself, but to be transparent.

Intellectual Humility and Where I Have Moved

Whenever I approach learning about and teaching difficult topics, I try to do so with that transparency as well as with intellectual humility (a willingness to learn and shift opinions).

My views on gun control are informed by policy, by Jewish ethics, and by lived experience. I have listened to counterarguments for years. I have taught them. I have engaged them in professional and personal dialogue.

In the case of gun ownership by civilians, every dataset, every Jewish text, and every community story I have encountered reinforces my existing family bias.

However, what has shifted is my tightly held assertion that only law enforcement should be able to have guns. I don’t believe we will reach that reality in this country and therefore I believe that all of the safety measures I outlined above, must be enacted expeditiously.

Jewish tradition does not glorify weapons. It regulates them. It restrains them. It treats danger as a communal responsibility. If our response to threat is out of fear and not out of wisdom, this makes us less safe, it is not protection. It is panic.

Judaism, and my grandfather’s legacy, asks more of me than that.

Leave a comment