The Work of Adding Our Spark to Everyday Items

In the early 2000s, when I was working at Congregation Shearith Israel in Dallas, Rabbi David Glickman gave a sermon that has stayed with me for more than two decades.

He began, unexpectedly, with Harry Potter.

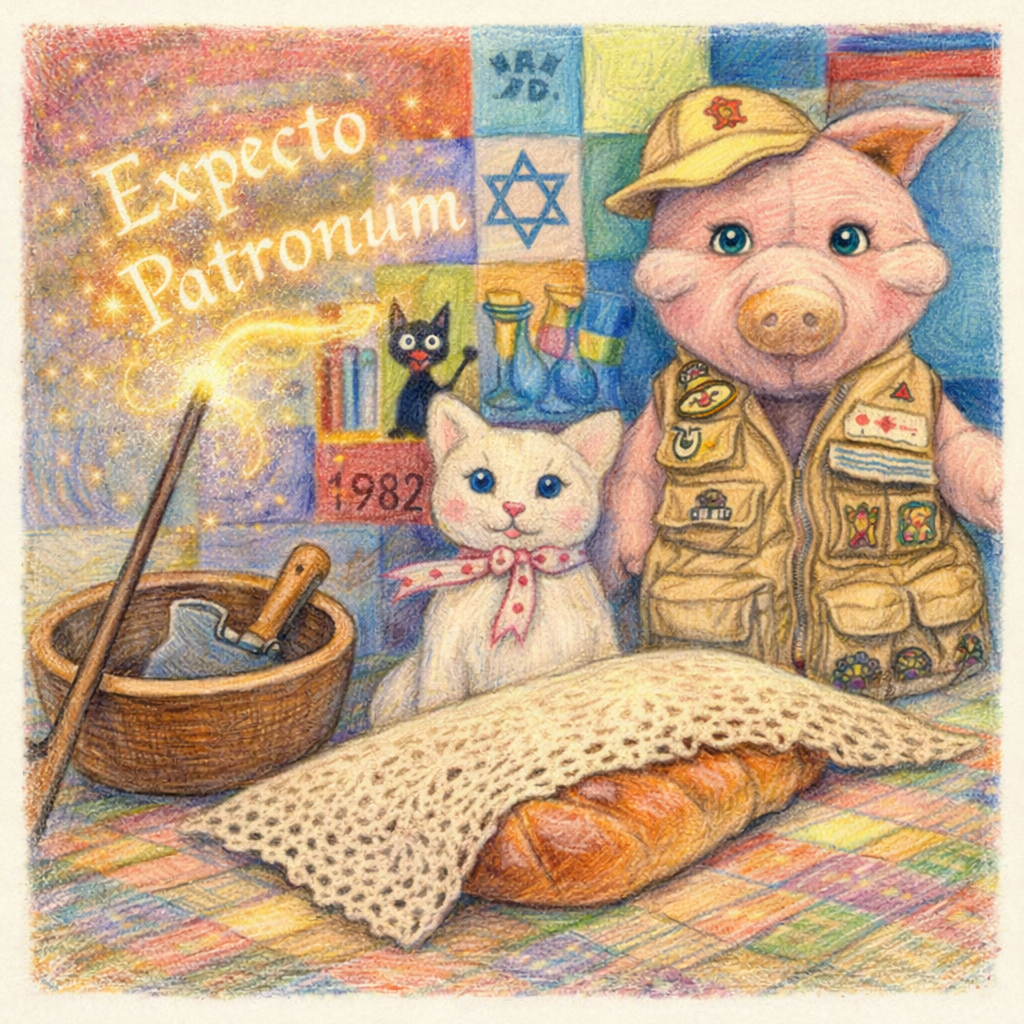

He talked about how, because Harry was a wizard and not a muggle, he could access and see magic in objects that appear ordinary to muggles: a stick is seen as a wand, a broom is seen as a flying machine and not a tool for cleaning, and a hat isn’t used for fashion or warmth but as an object that can read your soul. These objects are extraordinary not because they are inherently magical, but because someone knows how to access the magic by casting a spell and adding magic into them through intention, practice, relationship, and “blessing.”

Then he pivoted.

Judaism, he suggested, works the same way. Except instead of magic, we add holiness.

The sermon was given on the High Holy Days, which leads us into Sukkot, a holiday built entirely on this idea. Rabbi Glickman suggested that a sukkah is not holy because of its materials. It is temporary, fragile, and exposed. It is often made of bamboo poles, tarps, and leaf-woven beach mats.

A sukkah becomes sacred only when we sit in it, eat in it, pray in it, and sleep in it. Holiness does not descend upon the sukkah. We bring it with us.

That framing leads to a question many of us implicitly carry. If holiness comes from use and intention, why do Jews care so much about ritual objects themselves? If any random cup can hold wine or juice for Kiddush, why do we search for ornate kiddush cups? Why do families treasure beautiful (sometimes tarnished) candlesticks, embroidered challah covers, or even messy Channukah Menorah art projects made by children in religious school?

Judaism actually offers three distinct ways of thinking about ritual objects, and the relationship between them matters.

First, there are objects that serve a commandment, known as tashmishei mitzvah. These objects are not holy by nature. They become sacred through use. Two candles in plain glass holders on an ordinary table become sacred Shabbat candles when we light them, cover our eyes, and recite the blessing. The object’s role is functional. Holiness emerges through the act itself.

But Judaism does not stop at functionality.

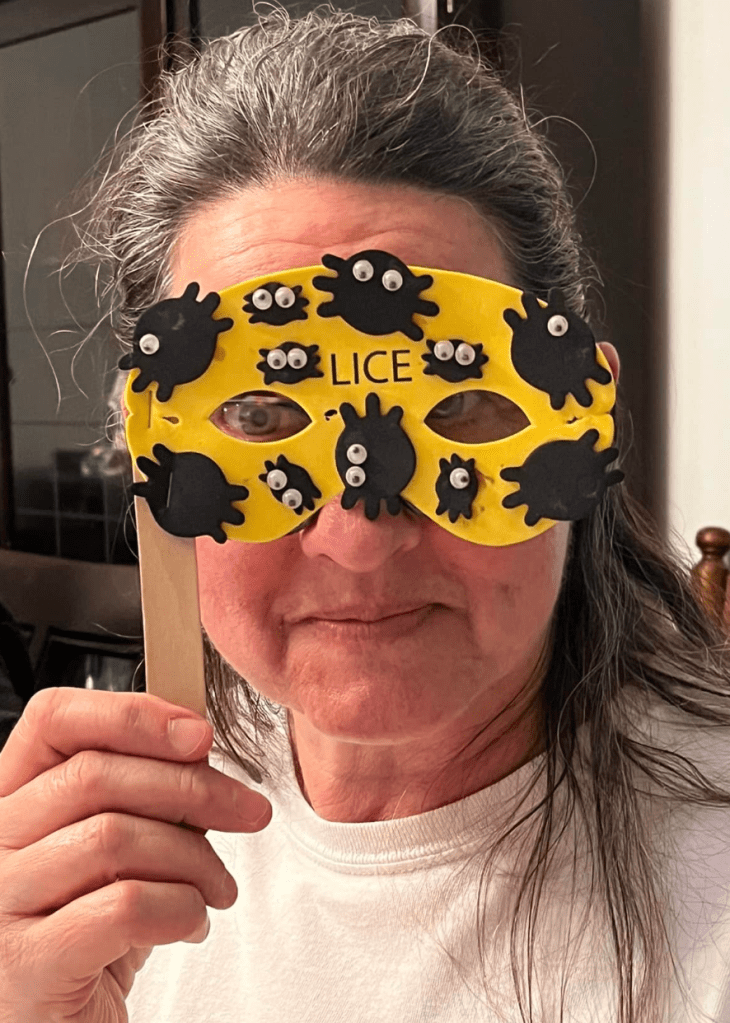

We are also taught hiddur mitzvah, the obligation to beautify a commandment. While a plain cup would technically suffice for kiddush, Jews have long chosen not to stop at “enough.” We seek the most beautiful etrog we can afford. We pass down elegant, antique kiddush cups. We proudly place child-created art project matzah covers and seder plates on the table year after year. Beauty does not create holiness, but it deepens our experience of it. Choosing beauty is a way of signaling that ritual matters, that it deserves care and attention.

[If you want to make some of these fun examples, here are links: Matzah Cover. Kiddush/Elijah/Miriam Cup. Felt Seder Plate.]

–> Our family plague masks are “sacred”

There is, however, a third layer, one that often goes unnamed.

Beauty does not come only from craftsmanship or expense. It also accumulates over time through memory, story, and repetition. Objects become beautiful because of what they have witnessed. This is where zakhor, remembering, enters. In Judaism, remembering is not passive. It is an obligation. We remember in order to carry something forward. Memory transforms an object from something merely useful or decorative into something that holds responsibility.

Taken together, these ideas form a progression. An object can fulfill a mitzvah. An object can be chosen for its beauty. And an object can become beautiful because it carries the weight of lived experience.

This is not only a theological claim. It is something I encountered repeatedly in my doctoral research.

In studying how under-engaged Jewish teens articulated Jewish identity, I paid close attention to the objects present in their homes, assuming that visibly Jewish artifacts would signal Jewish meaning. What I found was more nuanced. As I wrote in my dissertation, “the presence of Jewish objects alone did not indicate Jewish meaning-making.” Objects mattered only to these teens when they were embedded in story, memory, and repeated family use. An item became significant not because it was recognizably Jewish, but because someone could explain where it came from, who it belonged to, and why it mattered. Objects disconnected from narrative often faded into the background, while even ordinary items took on deep significance when they were actively woven into daily life.

This helps explain why certain objects hold such power in communal memory.

At United Hebrew Congregation in St. Louis, there is a chair that once sat in Rabbi Jerome Grollman’s office. When Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. spoke at the synagogue in 1960, during a period of relentless travel and organizing, he reportedly rested briefly in that chair. Each year on Martin Luther King Jr. weekend, the congregation places the chair on the pulpit.

The chair is not ornate. It is not ritually designated. Its beauty lies in what it represents. By placing it at the visual center of the sanctuary, the community chooses to remember what it witnessed and what it is obligated to carry forward. The chair functions as zakhor. It is an everyday object made holy through memory and moral responsibility.

I came to understand this same dynamic in a deeply personal way after my mom died and I was tasked with cleaning out our family home of 50 years.

In the months that followed, I found myself looking for ways to let pieces of her life continue to live with us. Like many families, I was less interested in preserving objects untouched than in allowing special ones to remain present.

My mother had dozens of T-shirts, accumulated over years of life and travel. They represented her hobbies, her vocation, her volunteer work, her physical journeys, and her relationships. I had them made into quilts for my two nephews and for myself. She had a fuzzy white robe she wore constantly, especially in the mornings when she made the boys breakfast during sleepovers. Because we are a cat family, I had the robe made into stuffed cats, one for each of the boys and one for me. Around each cat’s neck is a ribbon made from Valentine’s Day pajamas she wore every year.

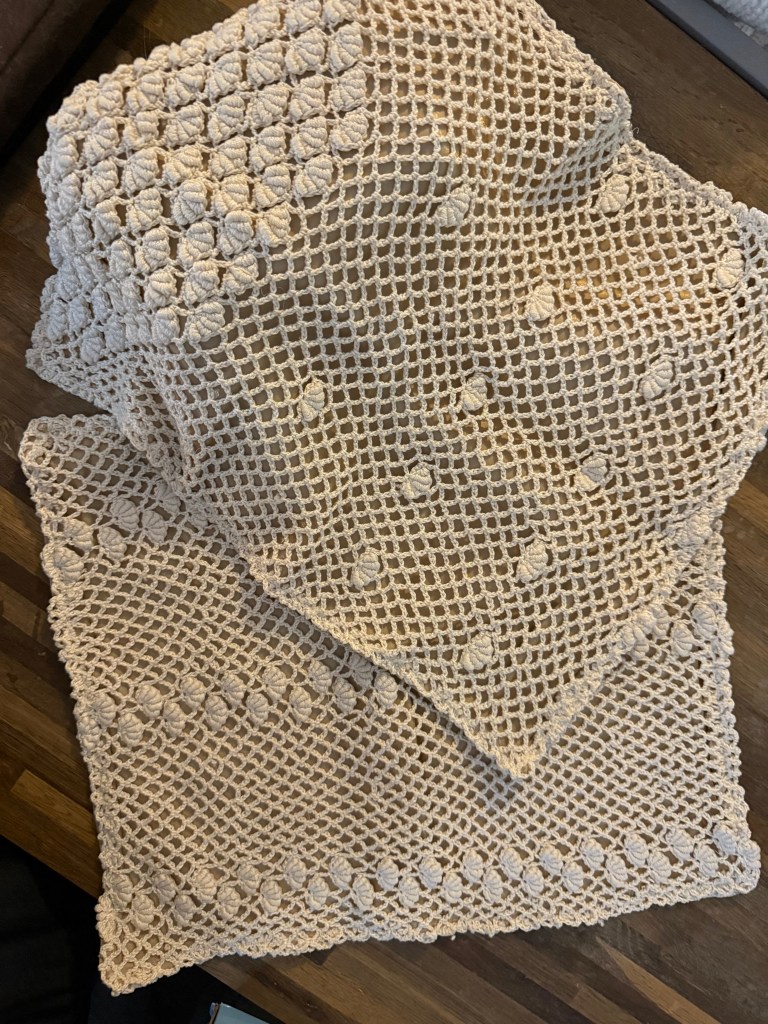

The most meaningful transformation involved an outfit she wore to my bat mitzvah and later to my oldest nephew’s bar mitzvah celebration. It was a champagne-colored macramé skirt and top. I had that fabric made into challah covers, one for me and one for each of the boys. Theirs are put away for now, waiting for a future moment of transmission.

How does a skirt and top become beautiful, beyond the craftsmanship, in this way?

Not because of the fabric itself. Because of the story it carries. Because it now sits on a table where blessings are recited, where bread is broken, where memory is renewed. Each time it is used, its beauty deepens.

The same is true of my maternal grandmother’s wooden bowl and chopper she used to make a few family favorite foods: charoset, chopped liver, and an eggplant dish she called kakeputze. After she passed in 1983, our family continued to use that bowl and chopper for the same recipes. It is now in my kitchen in Atlanta and used for the same. They are not sacred because they are antiques. They are sacred because they are still used, still present, still part of our family’s living story.

Judaism does not ask us to revere objects for what they are. It asks us to notice what we do with them. Holiness emerges when we use objects with intention, when we seek beauty as an act of care, and when we allow memory to transform the ordinary into the sacred.

There is another object in my home that on first glance would not only not appear sacred, but would likely raise an eyebrow or two. When I was in elementary school, my father won a giant pink pig for me at a local community carnival (photo left top is from the day he won it). I took it with me into every home I have ever lived in. After my father died, I placed his birdwatching vest over the pig — a vest covered in patches from years of extensive bird watching trips, careful documentation, and quiet attention — and added a St. Louis Cardinals hat, a symbol of our shared devotion and countless conversations. (Photo bottom left of it now.) The object did not become sacred because of what it was. It became sacred because of what it holds and what it represents.

Lately, I find myself wondering which objects my nephews will one day carry forward, and which stories they will choose to tell. Perhaps it will be something I recognize, like the stuffed frogs, Matzah Man (he sings and dances), and plague masks which have adorned the Seder table for the entirety of their lives, or maybe one of the Channukiot they claimed from my parents’ home as I was cleaning it out. (See slide show below of examples of all of these items in use over their lives – now 19 and 21 years old.) Or perhaps it will be something entirely their own, an object I cannot yet imagine but whose meaning will accumulate through their lives. What matters is not whether I anticipate it correctly, but that they will know how to recognize it when it happens and they will know how to notice when an ordinary thing begins to carry memory, how to tell its story, and how to pass it on not as an heirloom to be preserved, but as a vessel meant to remain in use.

Like magic in a story, holiness does not appear on its own, we must be the wizards and see its potential and add the sacred spell.

Leave a comment